Beware of the pseudo-messiahs

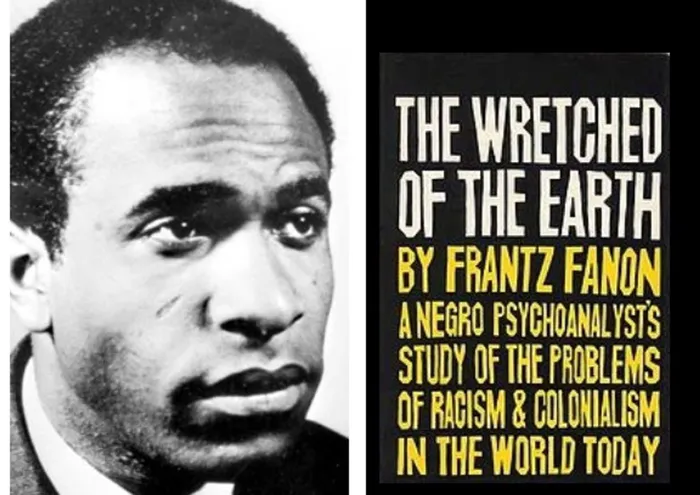

The writer says South Africa can learn from Frantz Fanon's book 'The Wretched of the Earth' about the mistakes of other African nations. The writer says South Africa can learn from Frantz Fanon's book 'The Wretched of the Earth' about the mistakes of other African nations.

South Africa is in trouble; and we cannot continue deceiving ourselves that things are normal by burying our heads in the sand like ostriches. This country is facing many challenges, with many new pseudo-messiahs cropping up all over the place promising to take South Africans to a new land of milk and honey.

How do you explain the psyche of many millions of South Africans who are excited about Julius Malema, even with claims that he made millions of rands through the exploitation of dodgy tenders, being their new messiah for clean government?

How do you explain a situation where communities hold the future of their own children to ransom by closing local schools for many months, as a way of forcing the government to build new roads?

Can these communities who are deliberately destroying the future of their own children on the misplaced belief that if they hurt their own children the public office bearers will react better, hence justify their unjustifiable behaviour on grounds that there is no gain without pain?

Vast human effort, financial resources and time have been spent by public office bearers trying to protect each other’s gross misdoings and/or corrupt behaviour to the detriment of focusing on the challenges of essential service deliverables. When these things happen, most people ask themselves if this is what the South African liberation struggle was all about.

We need to start seriously addressing the psyche of the post-apartheid South African to see if there is anything we can still do to reverse this rapid slide into political anarchy we are observing in our country. I was therefore happy to receive an invitation to the second Steve Biko Awards for Psychological Liberation, to be held at the Durban City Hall on September 16.

Constitutional Court Deputy Judge President Dikgang Moseneke and Steve Biko’s son, Nkosinathi, will confer the Steve Biko Award for Psychological Liberation on the late Frantz Fanon posthumously. It is also at this gathering that the Pan African Psychological Union will be launched, with representatives from the rest of the continent.

I am neither a psychologist nor a Pan-Africanist; but I urge everyone who can afford the time to go there to attend because, I believe, the time has come for South Africans to seriously consider the implications of everything going on around this country; we cannot just wish away many of these worrying danger signs.

Why are Algerian Frantz Fanon’s writings important to us, when he died long ago in 1961, when he was only 36 years old, and the country he came from is now neither an economic powerhouse nor a political heavyweight?

My interests in Fanon’s writings are based on the fact that he was a professional psychotherapist who exposed the connection between the colonial wars and mental disease, and went on to try to show how fighting for freedom needs to be strategically linked to national culture.

My problem with post-apartheid South Africa is that it is a pretentious country where we pretend there is neither the lumpen proletariat, nor the petty bourgeoisie, nor the bourgeoisie classes. We try to pretend that this is a classless society where the constitution guarantees us equality that ensures that anyone can be a leader anywhere, in anything, and anyhow. The problem with this pretentious egalitarian misconception is that we, as a nation, have not invested enough thought or the resources in ensuring that we educate everyone who wants to be a leader about what South Africa needs for this country to move forward.

When you observe the calibre of people who populated the national Parliament and the provincial legislatures at the beginning of this post-apartheid democracy you will quickly notice that the very first national Parliament and provincial legislatures comprised a carefully planned range of people from different walks of life, with a conscious decision to have sufficient people with intellectual skills to cope with the various challenges of understanding the political and economic mandate of the public office bearers. Unfortunately, we have seen, over the past 20 years of democracy, the gradual “dumbing down” of the calibre of those who represent us.

A casual profiling of who is likely to make it higher up the political party lists shaping who is going to the national Parliament, the provincial legislators, and the local government structures, shows it is easier for the vocal trade unionists and those who toyi-toyi the most to get ahead than those who try to be pragmatic about how to get the country economically successful.

That’s the price we all have to pay for democracy. Unfortunately, when the lumpen proletariat and the petty bourgeoisie refuse to accept that they have something they can learn from the bourgeoisie then you have the problem; because if those who lead now cannot learn from the mistakes of those who led before, you will have the same mistakes being repeated time and again.

Fanon wrote as early as in the late 1950s to very early 1960s that “…we have seen that the national bourgeoisie of under-developed countries is incapable of carrying any mission whatever. After a few years, the break-up of the party becomes obvious, and any observer, even the most superficial, can notice that the party, today the skeleton of its former self, only serves to immobilise the people”.

It is at this stage, Fanon observed, that the free-for-all self-enrichment begins to the detriment of the country.

Is it not time we all go back to reading Fanon’s book The Wretched of the Earth, Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, and similar literature, to learn from the mistakes of our African continental counterparts, and sort out the avoidable problems in South Africa, without being populist?

Or would we rather have a second South African revolution led by ideologues who will shout big revolutionary slogans while taking South Africa into serious poverty and economic regression?

Unfortunately, if those people in South Africa who are able to think pragmatically and intelligently decide to keep quiet and not stand up to be counted this country will be lost to those with the loudest mouths and the biggest appetite for corruption; and that second South African revolution will be directionless and as counter-revolutionary as the military coups we have seen in Lesotho, where the people with big guns think they can just run the country without knowing what to do with the political power they have just given themselves.

Dumisa is an independent economic analyst, an advocate of the High Courts of South Africa and Lesotho, and a former university Professor of Management