From ghetto to big screen

Scenes from Joram. Pictures: Supplied

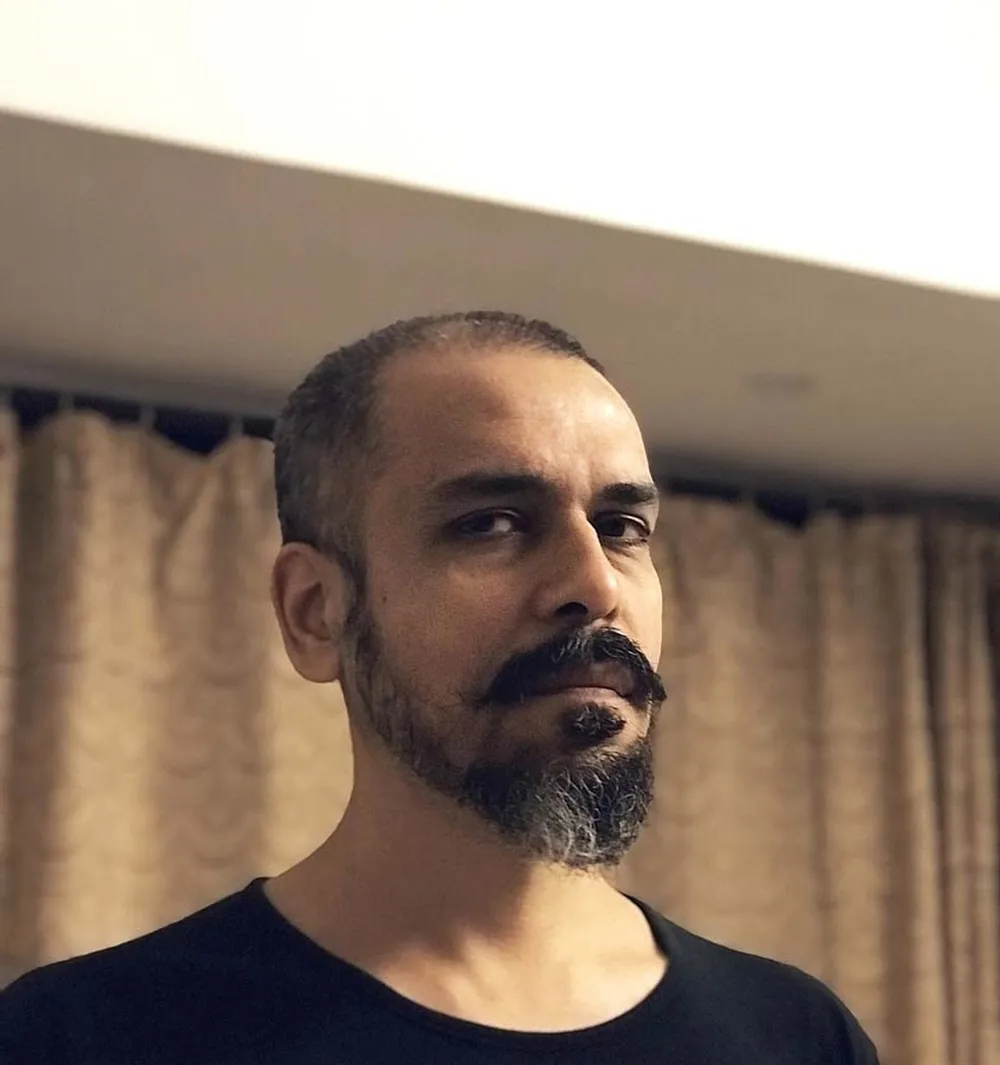

IT was his early years growing up in a Sindhi refugee family that were to shape film-maker Devashish Makhija’s stories.

His journey into the field includes a major career change, having to sleep at railway stations and surviving on one bun-and-tea a day during his early years in the gruelling industry.

Today Makhija’s stories have earned him respect. His feature film, Joram, will screen at the 44th Durban International Film Festival which began in Durban on July 20, wrapping up on 30 July.

According to the plot: Dasru and Vaano lead an anonymous life as migrant labourers on a Mumbai construction site with their infant daughter, Joram. A brutal turn of events compels Dasru to cradle Joram in a sling and flee for the distant forests he had once run away from for answers, and survival.

Soon he has Mumbai cop Ratnakar in pursuit. Torn between duty, systemic victimisation, and the gradual realisation of how he is probably just a helpless outsider to the inner machinations of development at any cost, Ratnakar finds himself shifting from pursuer to witness in an endgame that seems like it may grind him to dust – as it must have thousands before him.

The film stars Manoj Bajpayee, Tannishtha Chatterjee, Mohammad Zeeshan Ayyub, Smita Tambe and Megha Mathur.

Born in Kolkata, West Bengal, Makhija said his parents were born in what was now called Pakistan, before the partition in 1947, during which they were part of the exodus into what is now called India.

“We are a Sindhi refugee family that ended up in the state that speaks Bengali. Now I live and operate in Mumbai (previously Bombay) in the state of Maharashtra, where Marathi is spoken.

“I am a cultural, linguistic refugee within my own country – a paradox that is both complicated yet exciting for the perspectives it continues to throw up. This sense of displacement deep within informs all my stories and films.”

He studied science in high school in Don Bosco School in Kolkata (which was then called Calcutta), and then studied economics in St Xavier’s College.

“I almost started my Master’s in economics but then realised my heart lay in the arts,” he said.

The 44-year-old creative said: “I felt a fire within me each time I did something artistic/creative right from when I was a child. Back then in the 1990s in India, a teenager was not exposed to enough options for what path to take in life. My family was a simple refugee family getting by on little in a ghetto in central Calcutta. Following the arts as a profession did not even occur to me growing up. Until I tried it all – almost studying for my Master’s, and even cracking the top exam for the MBA – and then suddenly walking away from it all because it just felt wrong deep inside.”

Makhija continued: “I was an illustrator, a cartoonist, an author, a poet, a musician, a dancer, a performer, all of those things. But I was not a cinema buff. I started working in advertising, not knowing what else to do, where I stumbled upon some cinema-crazy Bengali colleagues. Over a year, I slowly discovered that there was this medium where I could express myself through writing, image making, performance, music, photography – all of the above and more. That was the primary thing that drew me to cinema.

“Meanwhile, my mother had cancer. I was her primary caregiver through my college time and two years of my short advertising career. When she passed, something inside me crossed a threshold, broke out of orbit – I got into an unreserved train compartment, leaving my father alone in our decrepit life back in Calcutta – and blindly headed to Bombay to test my fortune.

“I didn’t want to go to Bombay as much as I wanted to put as much distance between myself and Calcutta as possible. And Bombay is literally on the western edge of the country, the other end from Calcutta, which is on the eastern edge.

“Many difficult years followed – during which I have slept on railway stations, got by on one bun-and-tea a day, watched dozens of my scripts and films get shelved after starting – but something about the promise of what I could do with my rage and stories through cinema kept me going,” he said.

Makhija said he was petrified when he made the decision to go to Mumbai to pursue his passion in film.

“I was petrified, because I’m naturally a shy introvert. It takes a lot for me to speak to strangers, let alone chart a journey in a massive, intimidating new city to which several thousand Indians flock every single day with dreams in their hearts.

“My biggest fear was not being able to provide for my old, lonely father back in Calcutta, because – being a rootless refugee family – we owned nothing, not even a home. We have lived our lives on rent, even the small shop he sold garments from. And ultimately I couldn’t.

“I chose the road to artistic cinema, in a city that celebrates and nurtures the commercial cinema. My films are informed by this dissatisfaction and dislocation, perhaps. My father had a difficult passing, with dementia, alzheimers and eventual Parkinson’s. My previous film Bhonsle was in some way a tribute to the difficult life he lived alone, searching for meaning, waiting for a hopeful exit from it.”

Throughout some of the topics explored in Makhija’s different works, issues like fear (related to terrorism), lust/desire, loneliness, regret and more, are portrayed through real-life stories.

POST asked what was it about authentic voices and human emotions that inspired him.

“I don’t know if the word to use is ‘inspire’. Perhaps I use these stories of the ‘others’ to invoke, manifest these exact things you mention that lie deep within me. I feel constant fear on behalf of the targeted classes in this country. This country has failed them. The democracy we claim is enshrined well enough on paper. But in exercising those same principles we fail every day. And it is those who are not represented strongly enough in the corridors of power that pay the price in all kinds of horrific ways.

“Their stories interest me the most. I feel unmoved and disinclined to even watch films about the minor struggles and heartache of the privileged classes. There is too much inequality in this country (more than other countries I feel, since we are such a messy heterogeneous mix of so many cultures, languages and regions).

“Those at the wrong end of this inequality – it is their voices, concerns, emotions, battles that move me and interest me the most. Perhaps I vampirise their emotions to express my own rage and resentment at how intolerant and impatient we have become as a species,” said Makhija.

Commenting on “Joram”, he said tribal rights have always been a motivating passion.

“I have been involved in tribal rights for years. The indigenous in India are so far down in the food chain that they become the first collateral for any development the country needs. Their perspective is disregarded. Their rightful dues are often deprioritised. And they are subject to so much violence from so many quarters that counter-violence sometimes becomes a desperate, unavoidable response.

“This almost never makes it to our mainstream discourse. People in the cities are wilfully, and blissfully, ignorant of the incredibly complex fabric of this situation, even if they maybe living right next to a mineral-rich forest where such a narrative of violent displacement is playing out right then.

“My first feature film – which disappeared without a trace – Oonga, was around these issues. I rewrote it as a Young Adult (YA) novel, which won the country’s top literary award for YA fiction two years ago. I’ve made a much travelled short film around this situation too – Cycle. Along with two children’s picture books, and endless short stories (some of which are in my anthology Forgetting) too. All of these were perhaps building up to Joram,” he said.

“All those themes, and the complexity of the multiple perspectives in such a situation, found their way into the intricate weave of the fabric of Joram. It is very difficult to decide which side of the line you may be on. I’m not blind to the irony of enjoying the fruits of this development, which displaces the indigenous from the land they have inhabited for thousands of years. I’m typing this on a laptop that has parts made of steel and aluminium, both of which are extracted from iron ore and bauxite which comes out of Earth that is made to bleed – both literally and metaphorically.

“Joram is an attempt to hopefully understand these paradoxes, and raise questions about the blindly greedy species we have become, and what legacy we are (unwittingly?) leaving for the rest of us to come,” he said.

Makhija has written and directed the multiple award-winning short films Taandav, El'ayichi, Agli Baar (And then they came for me), Rahim Murge Pe Matro (Don’t cry for Rahim LeCock), Absent, Happy, Cycle and Cheepatakadumpa; and the full-length feature films Ajji (Granny) and Bhonsle.

*Joram will screen at July 22 at Suncoast at 7.45pm, and on July 28 at 8pm. Tickets can be booked at cinecentre.co.za