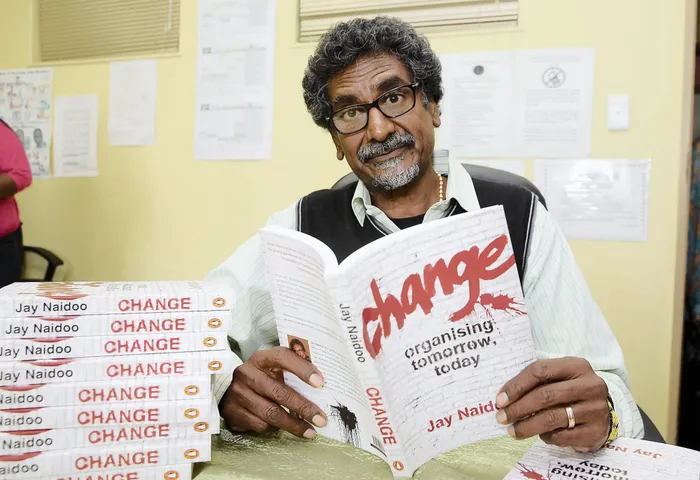

Former minister Jay Naidoo at the launch of his book, Change: Organising Tomorrow, Today, in Phoenix earlier this month. Picture: Motshwari Mofokeng/ANA PIctures Former minister Jay Naidoo at the launch of his book, Change: Organising Tomorrow, Today, in Phoenix earlier this month. Picture: Motshwari Mofokeng/ANA PIctures

June 16, 1976 signalled a decisive epoch in Struggle history and captured the unique role played by our youth in the struggle for national liberation and rebuilding of a new South Africa.

It is now accepted that every year on June 16 we pay tribute to the class of 1976, either by visiting the iconic grave of Hector Pieterson in Soweto, to bemoan the current state of the youth or by holding commemorative events, to reminisce and recount the tragic events of that day.

What has not been told is that scholars have consistently argued that the Soweto Uprising of June 16 owes its origins to the 1973 Durban Strike.

By highlighting this, one is not trying to misappropriate history but connecting the dots. One of the principal leaders of the Durban Strike was celebrated trade unionist and Communist Johannes Nkosi. This heroic strike led to the rebirth of progressive, radical and militant trade union activism in South Africa, which in turn influenced the heroic youth of 1976.

The bravery of the youth of 1976 led to the swelling of the ranks of the liberation movements in exile, bringing fresh vigour and adding tempo to the Struggle for liberation and people’s power.

It is no coincidence of history that the student-worker axis in the early 1980s rejuvenated progressive politics and brought a breath of fresh air, which led to the formation of the union federation Cosatu

and the United Democratic

Front (UDF).

It was through this axis that the Struggle was renewed and the world paid attention to battle being waged by the people of South Africa for a new order.

The images of jailed leader Nelson Mandela and decorated symbols of black, green and gold of the ANC were increasingly profiled and those involved in activism associated themselves openly with the liberation movement, as led by the ANC.

This worker-student axis was a vital cog in rendering the apartheid regime ungovernable as called for by then ANC president Oliver Tambo in exile.

PW Botha’s regime responded to the uprising by declaring a state of emergency.

A significant number of activists were detained without trial; police brutality escalated; others disappeared without trace by their families, with many being killed and buried in unmarked graves.

But the resilience and steadfastness of the youth brought

hope to the oppressed people of South Africa.

It is not surprising that the heroic victory of MPLA/MK joint forces against the apartheid SA Defence Force at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale marked a watershed moment, which heightened the revolutionary seizure of power by the ANC in 1994.

The dastardly assassination of Chris Hani forced the apartheid regime to concede defeat, even though his tragic killing was meant to plunge the country into a civil war. From Boipatong (Sedibeng) to eMbumbulu (south of Durban), the youth was armed and ready to avenge Hani’s death. He occupied a special place of pride, commanded respect and was an exemplary figure among the working class and poor youth.

The fighting youth still had deep scars and unhealed wounds since it was at the receiving end of political violence that marred the country during the negotiating period to establish a democratic South Africa. A number of youth activists lost their lives in violent skirmishes between the ANC and Inkatha Freedom Party factions, notably in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal. At the height of the conflict, areas were regarded as “no-go” zones.

Since the negotiated political settlement of 1994, the nascent democratic state, as led by the ANC, declared June 16 a public holiday in remembrance of those who perished on that fateful day and subsequently to recognise different generations of youth who have left an indelible mark in history and played a heroic role in the Struggle.

Of particular significance, there has been a growing layer of youth drawn from sections of a rapidly upwardly mobile black middle class and an emerging section of the black capitalist class.

Unlike the 1976 youth, which was united to fight the oppressive apartheid system, the new democratic conditions have been accompanied by various aspirations and interests of the youth of today.

These find expression in social and economic standing; those youth from a middle class or capitalist background have greater opportunities, such as a better life, access to quality education, health and they are easily absorbed in the job market, whereas the youth from a working class and poor background are confronted by the harsh realities as a result of inferior education, a collapsing public healthcare system, poverty and underdevelopment.

In South Africa today, 48% of the youth between the ages of 15 and 34 are unemployed, amid the challenges of racialised poverty, deepening inequality and an escalating unemployment rate.

What is more concerning, since the economic meltdown or financial crisis of 2008 up to 2015, is that the number of youth that are too discouraged to search for employment increased by a staggering 8%.

Accompanying this ugly reality is an economy that is shedding massive jobs in the mining and manufacturing sectors.

Equally, those lucky to be employed are seized with the socio-economic burden of having a responsibility to feed and take care of the large army that is ravaged by hunger and poverty, mainly in working class and poor households.

Even though significant advances have been made by the democratic state to improve the lives of young people and accord them a better future, our stubborn economy’s inability to create much-needed jobs for the youth continues to be a big challenge.

It is within this context that the youth of today must heed Mandela’s words: “I have a wish to make. Be the scriptwriters of your destiny and feature yourselves as stars that showed the way towards a brighter future.”

This calls on the youth of today not only to be “scriptwriters of their destiny” but also to engage in struggles for the attainment of the goals of the Freedom Charter as a “way towards a brighter future”.

It is an undeniable fact that the future of the country’s youth lies within the implementation of the Freedom Charter by our democratic state.

As dictated in the Freedom Charter, the breaking down of monopoly industries in strategic sectors to allow greater participation and ownership by the black majority, provision of free higher education and redistribution of land can lead significantly towards the creation of decent jobs and an end to economic exclusion and marginalisation of the youth.

This requires the youth to organise itself as a critical and leading voice in society and forcefully push for a policy shift and introduction of progressive reforms that advance the key demands of the Freedom Charter.

As astute thinker and revolutionary figure Frantz Fanon wrote: “Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfil it, or betray it.”

Just like the generation of 1976 which had rightfully “discovered its mission”, and fought gallantly against a system that was declared a crime against humanity, apartheid, the current generation has a revolutionary obligation and duty to “discover its mission, fulfil it, or betray it”. History is on the side of the youth!