Craving spinach after the Fukushima scare

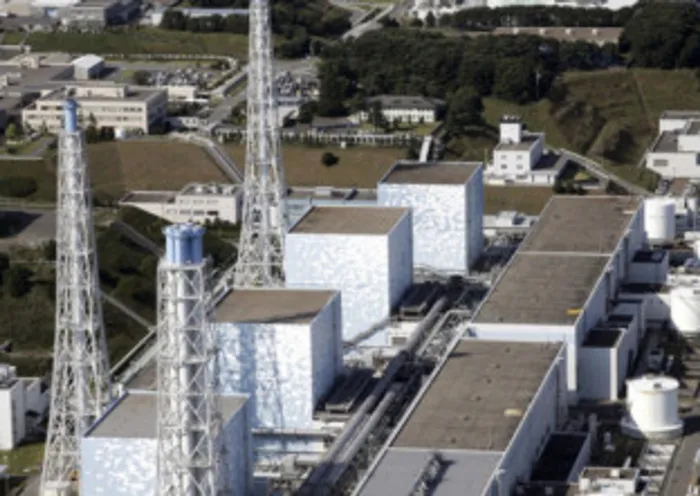

An aerial view of Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant in this October 2008 file photo taken in Fukushima Prefecture, northeastern Japan. An aerial view of Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant in this October 2008 file photo taken in Fukushima Prefecture, northeastern Japan.

Almost every Saturday, my family goes to a yaoya, or market that sells produce grown to meet Japanese consumers’ famously picky standards for tastiness, crispness and freshness.

We love the quality, but often wince at the prices. So my wife and I are looking forward to the day when we can enjoy cheap spinach from Fukushima Prefecture.

Yes, Fukushima is where the March 11 tsunami devastated a complex of nuclear reactors, leading to partial meltdowns and the spewing of radioactive matter into the environment. And yes, spinach from a wide zone around the nuclear facilities was one of the first crops found unfit for sale – an ominous harbinger for agriculture in one of Japan’s most bountiful areas.

Perhaps, then, my hankering for Fukushima spinach sounds like the bravado of a daredevil or nuclear power advocate. I am neither of those things.

Rather, as a resident of the vast metropolitan area including Tokyo and Yokohama that lies within a couple of hundred miles of the crippled plants, I have been trying to educate myself about the health risks – or lack thereof – facing my family.

The more I learn, the more hysterical the reaction abroad seems regarding the alleged dangers to anyone living here or venturing near. Hence my perverse glee upon finding out that leafy green veggies from Fukushima could conceivably be back on the market in a few months.

Early manifestations of the hysteria were relatively harmless. More troubling are signs that the jitteriness could undermine Japan’s recovery as the nation’s tainted image leads to a halt or reversal in its integration with the global economy.

Last week, Hapag-Lloyd, the world’s fourth-largest shipping firm, kept its vessels out of Tokyo Bay. Although few carriers followed suit, vessels coming from Japan face delays for extra inspections at foreign ports, a costly burden that some experts say may lead to the diversion of more shipping away from Tokyo.

The Japanese phrase gishin anki – roughly, “monsters in the darkness of doubtful minds” – captures the fears that fuel such behaviour. When it comes to radiation, most of us instinctively succumb to this syndrome – as I did when news broke about the damage to the plants. Envisioning lethal particles seeping into our house, I asked my wife, who is Japanese, where I could buy duct tape to seal our windows.

In days since, our anxiety eased as we watched the news on Japan’s public broadcasting network NHK.

Almost nightly, professors from leading universities have appeared on NHK to explain the degree of hazard that might be present in the air, soil and water. Their conclusions have been consistent: There is no cause for alarm among people living a substantial distance from the stricken plants.

The night that the Tokyo metropolitan government advised parents to stop giving tap water to infants, NHK anchors questioned Kenji Kamiya, the president of Hiroshima University’s Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine and an authority on the hibak usha (survivors of the atomic bombs).

A kind-looking man with white hair, Kamiya said although he understood why mothers would worry, a baby who drank some tap water should suffer no ill-effects, given the low levels of radioactive material found; he also assured mothers that they could safely continue breast-feeding.

Other nights, top academics in nuclear engineering have brought perspective to efforts to contain damage at the plant.

They have assured the public that even the worst plausible outcome would be a far cry from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, for a number of reasons. Chief among them is the fact that the Fukushima reactors shut down immediately after the earthquake, rendering impossible the massive explosion that occurred at Chernobyl.

Might all this be part of a monstrous conspiracy to suppress panic? Even believers in such far-fetched theories would have a hard time explaining what I found on English language websites and news reports: experts drawing similar conclusions to the ones on NHK and a virtual absence of reputable authorities saying the opposite.

Spinach provides an illustrative example. Radioactive iodine – the isotope responsible for causing thyroid cancer in thousands of children near Chernobyl – turned up at levels well-above legal limits in spinach samples from Fukushima.

Fortunately, the Japanese can take relatively simple preventive steps that the callous Soviet authorities didn’t.

According to a calculation by health physicist Peter Caracappa, you’d have to eat 372kg of spinach at the highest levels of contamination detected to increase your lifetime cancer risk by 4 percent. So while I wouldn’t relish eating a few chopsticks full of Fukushima spinach right now, I wouldn’t shrink in terror either.

People from Tohoku, the region where the tsunami struck hardest, are renowned for being even more stoical, selfless and community-minded than the average Japanese. Yet, admiration and sympathy for these people doesn’t mean foreigners are obliged to risk their own health.

If I thought my kids were imperiled, I would join the evacuation from Tokyo. But the people of Tohoku, and their compatriots elsewhere in Japan, deserve a better than the gishin anki treatment. It will be a privilege to eat their spinach. – Bloomberg

Paul Blustein is a researcher at the Centre for International Governance Innovation. These views are his own. Donwald Pressly is on leave.