CAPE TOWN – Against the backdrop of the pandemic Covid-19 (coronavirus), the Council for Medical Schemes (CMS), a division of the Department of Health, is once again in the spotlight with its continuing battle with primary and low-cost medical healthcare insurance providers, over its decision to ban them from providing such products in South Africa.

This is a move, which could leave around 500 000 members and their beneficiaries in the country, (up to 2 million people), without cover.

Given the global fallout over coronavirus and its potential to be more harmful than the Spanish Flu of 1918, is denying low-income households access to private healthcare, really the way to go?

Medical Health Insurers in South Africa provide low-cost primary healthcare insurance products for individuals who earn a minimum wage, and for others who cannot afford medical aid. Last year, the Council for Medical Schemes issued circulars 80 and 82 where an instruction was given to insurers of low-cost products, to cease operations by March 2021.

The Alexander Forbes Health team, on information portal eBnet.co.za (Digital Employee Benefits and Retirement Industry News and Knowledge Portal), suggested that this decision was taken jointly with the National Department of Health in order to align with the national health policy and more especially, the impending plan to implement national Health Health Insurance.

What Circular 80 of 2019 is essentially saying, is that it will be illegal for healthcare insurers to operate from March 2021, if the Department of Health’s CMS gets its way.

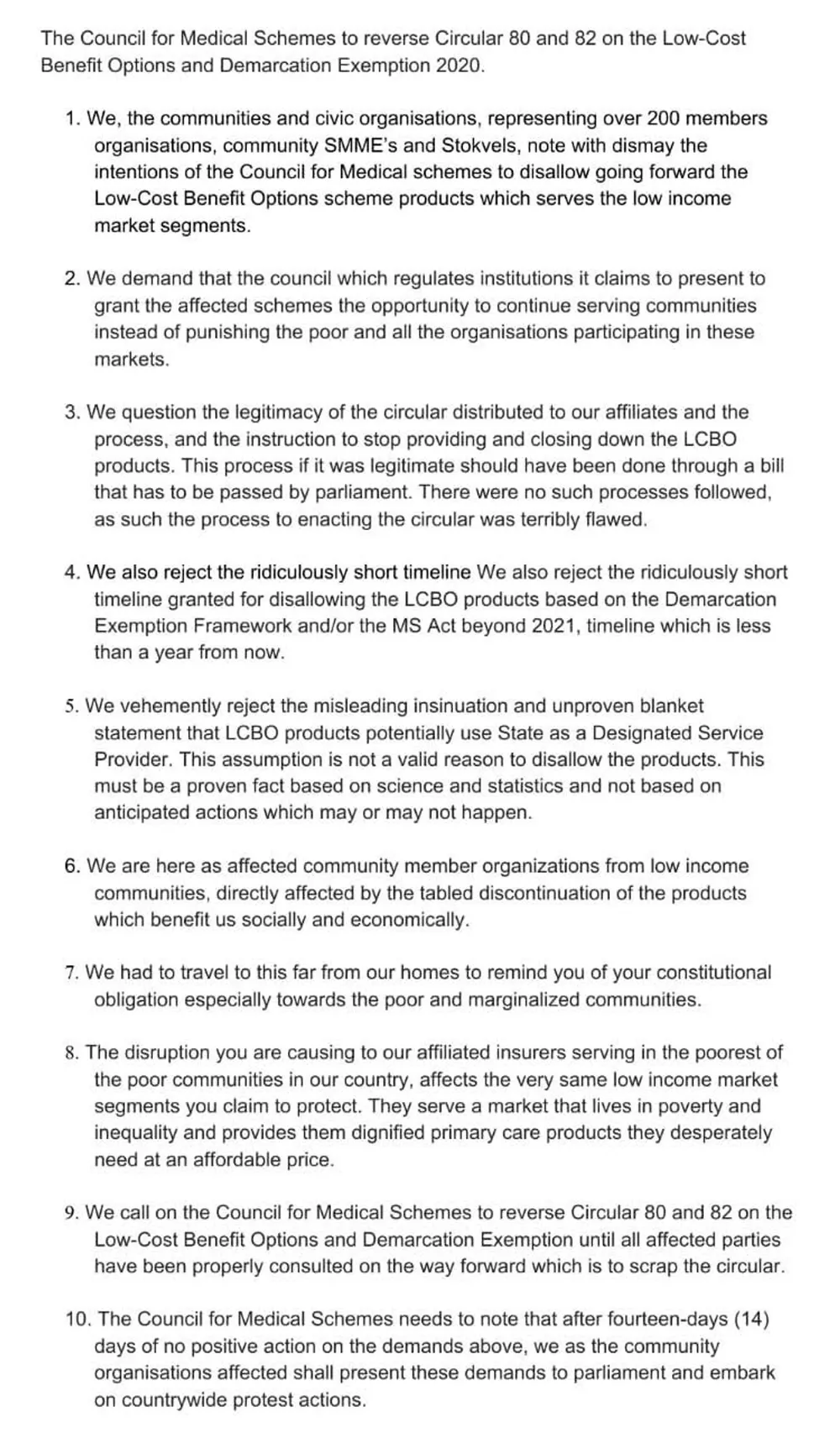

The move has been met with widespread condemnation from various civil society organisations and communities, representing more than 200 members and organisations, community SMMEs and Stokvels.

Buti Sigasa, the spokesperson of the Healthcare Stakeholders Forum, which represents civic organisations and businesses in the health insurance sector, said the Forum’s main objective would be to reverse circular 80 and 82 of 2019, which required low-cost health insurance products should be shut down.

“Health care insurance products are providing cover for low income earners. Their rationale is that the council is aligning with the National Health Insurance, which is yet to be implemented. The rationale is frivolous because the National Health Insurance is not in place and it will not be in place for many years to come. This will have a devastating impact on the economy and the industry as a whole,” said Sigasa.

Sigasa was also of the view that the impact, particularly in the outbreak of the coronavirus, or any other widespread healthcare concern were to occur post 2021, it would have a negative impact on workers who could not afford medical aid. It would also place an even greater burden on the government as those workers would be dependent on the state, not being in a position to access basic GP visits and pharmaceutical products.

“There are about 2 million beneficiaries and about 500 000 main members who are covered by low health insurance products. They will lose this cover and will have to be dependent on the state,” he said.

Currently, there are four funding mechanisms for healthcare in South Africa. According to Sigasa, the biggest and most overburdened, is the state, as it caters for the unemployed and those who are employed but, cannot afford medical aid cover.

The second mechanism is the medical aid schemes, which are regulated by the Medical Aid Schemes Act. Medical aid schemes are there to provide access to private hospitals and private health care for those with the means to pay for care.

“The third mechanism is what we call we call, healthcare insurance products. Unlike the second mechanism, this basically has what you call, ‘low cost’ options,” affirmed Sigasa.

He further explained that although some of these medical aids had applied for exemption from the Medical Aid Schemes Act - and some had been granted such exemptions - because health insurance products were seen to be doing the work of medical aids, there was a discussion between the Department of Health’s CMS, including the FSCA, which resulted in what is called ‘demarcation regulations’.

“The health insurance products are mainly for people who are dependent on the state but cannot afford medical aid,” explained Sigasa.

The fourth mechanism is what is termed as ‘sick funds.’ These are regulated by the labour department in terms of the Labour Relations Act. They are not subjected to prescribed minimum benefits (PMBs) unlike health insurance products.

Sigasa explained: “Sick funds are mainly found in bargaining councils, like the road freight bargaining council, which cater to low income earners, employers and trade unions”.

Sigasa also said the CMS’s decision will have far reaching consequences on the industry as brokers, administrators and actuarial scientists, accountants, and ordinary call centre workers will all be effectively put out of work.

“Low income workers will not be able to treat Covid-19 or the effects of Covid-19 if the CMS implements circular 80. People will not be able to provide healthcare for their families and will depend on the state. There will be job losses and doctors and pharmacies servicing these communities will also lose business,” he said.

Dr Sipho Kabane, the registrar of CMS said the regulatory body had internally developed a draft standardised benefit cover, which was more comprehensive than most product offerings in the market.

“This standardised benefit cover will be discussed in the advisory committees that we are establishing for this purpose with the industry stakeholders as per Circular 12 of 2020. This benefit cover will be accompanied by a set of proposed conditions including a framework that will need to be complied with by the service providers. We believe that this draft benefit cover and its framework are a proper vehicle to be used to migrate these products into the medical scheme regulatory environment,” he said.

He further explained that the implementation of the decision by the CMS with respect to whether these products will be allowed to operate beyond March 2021, is highly dependent on the engagements with the advisory committees.

“It is therefore important that all the affected stakeholders should participate in the advisory committee engagements. We believe that if these engagements are productive, they may indeed inform the decision by Council to determine whether they should be continued or not,” he said.

He said there was currently no confirmation that the affected members or beneficiaries are 2 million.

“We have on record approximately 500 000 beneficiaries. CMS is a responsible regulator, whose mandate it is, to look after beneficiary interests. This statutory mandate will not be abandoned by it, in the manner that it will deal with the affected policy holders,” he said.

BUSINESS REPORT