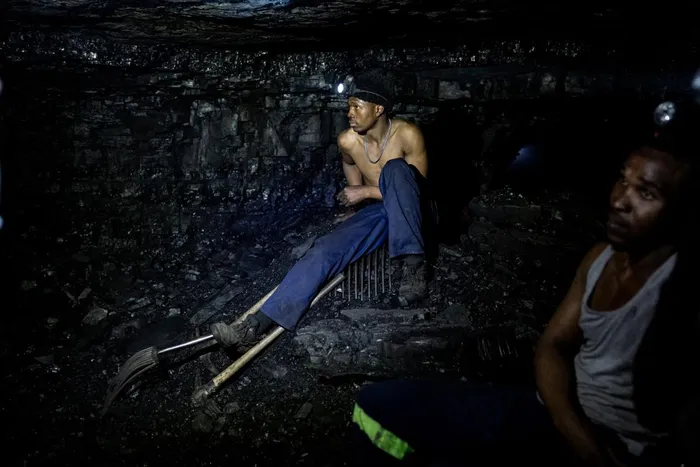

An artisanal miner looks on as he takes a break from collecting coal in a tunnel at the Golfview informal coal mine in Ermelo.

Image: AFP

Growing up, Cyprial dreamed of being a lawyer. Instead, he now spends his days underground, swinging a pickaxe against rock in a pitch-black illegal mine that snakes for kilometres beneath South Africa’s coal heartland.

The rumbling of wheelbarrows echoed down the narrow tunnels where he and dozens of other men had been mining since dawn.

Some chipped away at the rock face, their dim headlamps barely piercing the darkness.

Others pushed loads of up to 100 kilogrammes at full speed through the tunnels and up a steep hill to trucks waiting to deliver the coal to informal sellers in the nearby town of Ermelo.

Only a few tree trunks propped up the slab of stone forming the roof of the entrance to the mine, a hole in the slope of a gutted hill abandoned by a mining company in the eastern Mpumalanga province scarred by decades of coal extraction.

South Africa is among the world's top producers of coal, which fires about 80 percent of the country’s electricity.

Ranked among the 12 largest greenhouse gas emitters globally, the country became in 2021 the first in the world to sign a Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) deal with wealthy nations, worth $8.5 billion, to move away from dirty-power generation.

And while most of South Africa’s electricity comes from Mpumalanga, locals say they have benefited little from large-scale, formal mining and fear the transition to green energy might leave them behind again.

'Artisanal' or 'illegal'?

"Down the shaft, it’s pitch black. You cannot even see your finger," said Cyprial, taking a drag of a joint he said helped "take all the fears and shove them away".

Speaking under a pseudonym to avoid retaliation from authorities, he feared the illegal mine might one day collapse on him.

"Half of the youth from here in Ermelo are doing this job," he said.

Unemployment in Mpumalanga, at 34 percent according to the latest government figures, is even higher than the national average.

And even though coal from Ermelo powers cities across the country and abroad many locals lived in shacks with no access to electricity.

The government calls Cyprial and the others "illegal miners". But they prefer the term "artisanal mining", saying their work, though unauthorised, was essential to the local community.

"This coal, we transport it to communities so those people can use it to cook and to warm themselves," said Jabulani Sibiya, who chairs Ermelo’s artisanal miners' union.

The electricity produced in Mpumalanga is too expensive for many locals, he said. "It's not fair."

President Cyril Ramaphosa has called miners like these a "menace" to the country's economy and security, and authorities are trying to stamp out the activity.

Analysts estimate there were more than 40 000 illegal miners in South Africa in 2021, though most operated in abandoned gold shafts.

The formal coal sector, meanwhile, employs more than 100 000 people in direct and indirect jobs across the value chain, according to research from the University of Cape Town.

'Just transition'

Ermelo's artisanal miners have applied for a collective mining permit, but the process is costly and slow, said Zethu Hlatshwayo, a spokespersib for the National Association of Artisanal Miners (NAAM).

Earlier this year, the government introduced a draft bill intended to facilitate the formalisation of artisanal mining. But the process is bound up with red tape, Hlatshwayo said.

"You have to have land, permits, you have to do your environmental authorisation," he said. They also need a "rehabilitation fund" to later restore the land to its pre-mining state.

"All of that will take you to a good R3 million," he said, the sum being unimaginable for miners who lived "hand to mouth".

According to Hlatshwayo, a "just transition" to green energy requires that ordinary people also have access to South Africa's mineral wealth.

This would correct "the injustices of the past", he said, referring to the apartheid era when the lucrative mining industry was the sole domain of white South Africans.

"For us, 'just transition' means transitioning from a large-scale destructive form of mining, into a sustainable, artisanal and small-scale mining sector," he said, sitting in a vegetable garden that he tends with a local environmental NGO.

Activist Philani Mngomezulu, working in the same garden, pitched in: "Just one community mine, in the entire history of mining in this town -- that's all we're fighting for!"

The men said that mining would continue to exist even after the phaseout from coal, including for critical minerals needed for products from solar panels to electric cars.

But it was essential to "include sustainability, and artisanal and small-scale miners from the marginalised communities," Hlatshwayo said.

"It will not be a just transition if our people are left behind."

AFP