'Sad Girl' books: the trend that’s got us feeling all the feels - should we celebrate or worry?

In a world grappling with climate anxiety, economic uncertainty, unattainable beauty standards and the ever-looming pressure to perform and succeed, Gen Z and younger millennials are turning to literature that feels like them.

Image: Pexels/Nino Souza

From TikTok reels to #BookTok shelves at local bookstores, “Sad Girl” books have become the literary obsession of a generation.

These novels - often moody, introspective and emotionally raw - centre around young women navigating mental health struggles, societal pressure, alienation and the quest for identity.

But while some hail these books as honest portrayals of the modern female psyche, others worry they glamorise depression and self-destructive behaviour.

So, are “Sad Girl" books empowering or harmful? And what does their popularity say about the times we’re living in?

What is a “Sad Girl” book?

A “Sad Girl" book is a type of contemporary literature that centres on emotionally complex, often troubled female protagonists who are navigating the messy, painful and sometimes mundane aspects of life.

These stories are typically told from a first-person or deeply introspective point of view, with themes that revolve around mental health, loneliness, existential dread, female desire, body image, burnout, heartbreak and the search for meaning in a complex world.

These books aren't necessarily about "plot" - they're about mood and emotion.

And why are they popular?

The rise of “Sad Girl Lit" is no coincidence. It’s a product of its time - our time.

In a world grappling with climate anxiety, economic uncertainty, unattainable beauty standards and the ever-looming pressure to perform and succeed, Gen Z and younger millennials are turning to literature that feels like them.

Online, hashtags like #SadGirlLit and #FeministFiction rack up millions of views. There's also a rebellion against toxic positivity - this idea that people, especially women, must always be “okay”, always healing, always hustling.

“Sad Girl” books say: It’s okay to be a mess sometimes.

As with most things that go viral, "Sad Girl" books have their fair share of criticism.

Some psychologists and feminists argue that these books, in trying to depict raw emotion, risk romanticising mental illness.

Characters who refuse therapy, engage in self-harm, or wallow in apathy can be misread - especially by younger audiences - as aspirational or aesthetic.

Critics also worry that the genre might be too inward-looking, portraying sadness as a static identity rather than a temporary emotional state.

However, defenders of the genre argue that these books aren’t advocating for self-destruction - they’re documenting it.

They allow readers to sit with uncomfortable feelings, rather than rushing to fix or ignore them. And that, for many, is healing in itself.

The "Sad Girl" wave isn’t just a Western phenomenon.

South African writers are also engaging with themes of grief, alienation and womanhood in ways that echo - yet complicate - the global trend.

The "Sad Girl" wave isn’t just a Western phenomenon. South African writers are also engaging with themes of grief, alienation and womanhood in ways that echo - yet complicate - the global trend.

Image: Supplied

Here are a few titles that fit the emotional weight and introspection of the Sad Girl genre, with a local twist:

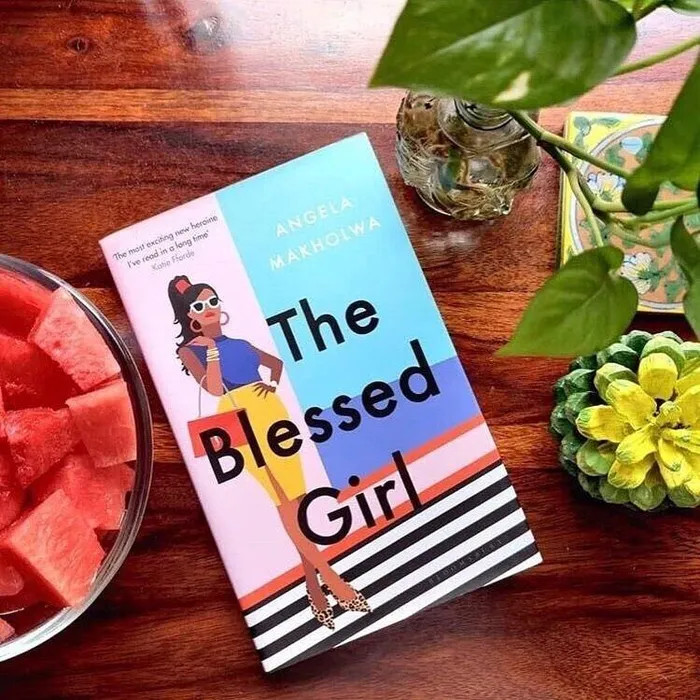

"The Blessed Girl" by Angela Makholwa

A biting, satirical, and darkly funny story about Bontle, a slay queen navigating sugar daddies, public persona, and private despair.

While flashy on the surface, it grapples with deeper themes of loneliness, trauma and identity.

“If You Keep Digging” by Keletso Mopai

This short story collection delves into the lives of ordinary South Africans dealing with everything from heartbreak to generational trauma.

Mopai captures the quiet melancholy of young people growing up in post-apartheid South Africa.

“Always Another Country” by Sisonke Msimang

A memoir that may not scream "Sad Girl" at first glance, but its reflections on belonging, exile and womanhood offer a more mature, grounded take on emotional and political identity.

Related Topics: