Britain's King Charles III (C) glances while standing beside US President Donald Trump at a State Banquet at Windsor Castle, on Wednesday, during the second State Visit of US President Donald Trump.

Image: ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS / POOL / AFP

Steve Hendrix

The United States and the United Kingdom were once the leaders on the global stage, the diplomatic duo tackling great crises.

Through two world wars, from Yalta to East Berlin to the Balkans, the sight of American and British leaders together signaled that a predictable order governed the affairs of nations. Self-interested, no doubt, but dependable democracies, anchored in the rule of law, whose collective power and iron will were welcome when countries were starving, freedom came under fire, or chaos claimed lives. Now, not so much.

Donald Trump arrived on Tuesday for his second state visit to the UK with the affairs of nations well out of his control, even more so the control of Britain’s prime minister - or its king. The pomp and pageantry of old is unlikely to reassure a world careening from crisis to crisis.

From the Middle East to the streets of Washington, from the steppes of Ukraine to the plains of Sudan, Trump’s visit unfolded against a backdrop of global division, disarray and destruction that no amount of ceremony can mask and no historic alliance has managed to address. Trade wars, real wars, democratic backsliding, technological disruptions - some are brush fires the president is charged with setting himself, others that he seems incapable or unwilling to put out.

“I don’t think most people are putting on the kettle and thinking ‘I’m so glad they’re meeting, all is going to be well with the world,’” said Nancy Koehn, a historian of leadership at Harvard Business School. “I don’t think most people look at these leaders and say these are the right guys with their hands on the helm working together for the well-being of the world,” she said.

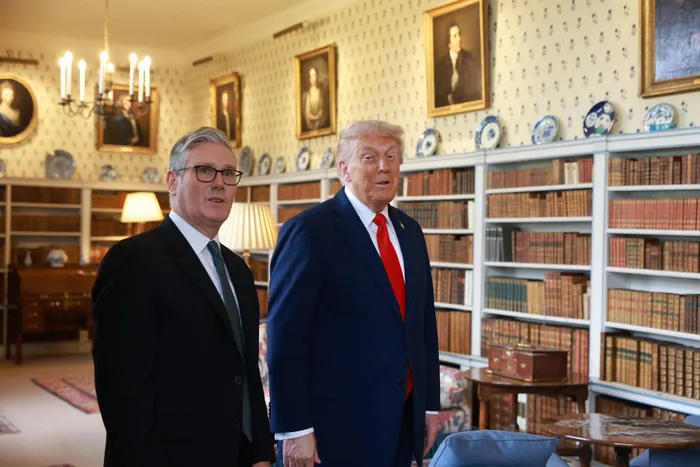

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer and US President Donald Trump at a bilateral business meeting at Chequers, England, on Thursday on the second day of the US President's second State Visit.

Image: Ian Vogler / POOL / AFP

Despite Trump’s promise that he would dispatch one of the worst emergencies within a day, Russia continues to clobber Ukraine. Following a presidential summit in Anchorage last month that fizzled into nothing, Moscow has ramped up attacks on Ukraine and expanded its drone sorties into Poland and Romania.

Keir Starmer, the prime minister who met Trump at his country residence, Chequers, has led a coalition of European nations supporting Ukraine whose most urgent imperative in recent weeks has seemed to be keeping Trump onside, rather than containing the Kremlin.

Israel’s war in Gaza rages unabated, with famine declared by a UN-backed agency in some areas and Israeli troops renewing attacks on Gaza City. Despite Trump’s on-again, off-again efforts to broker a ceasefire, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu targeted Hamas leaders in Qatar, the US ally that is hosting the negotiations. The strike on Doha came just under three months after Israel bombed Iran, derailing Trump’s efforts to negotiate a new nuclear deal.

Arab leaders warned Monday that Israel’s action in Qatar puts at risk the efforts to normalize ties in the region forged by the Abraham Accords from Trump’s first term. Rather than ending the conflict, Trump now faces an unraveling of his signature diplomatic achievement.

The very institutions that once provided stability - international alliances, multilateral agreements, shared democratic values - are now under strain from the same leaders who gather to celebrate them. Trump is widely seen as an agent of chaos in transatlantic relations, not so much its likely fixer.

The US and Britain also have sharply divergent views. Starmer has said the UK will recognize a Palestinian state unless Israel meets certain conditions, which drew a rebuke from Trump that it was “rewarding Hamas.”

One thing the American and British leaders share is that they are deeply unpopular. Such disdain explains why the Trump visit was a remarkably cloistered affair, almost entirely confined to Chequers and Windsor, far from the protests expected in central London.

Nor did 20th century leaders have to contend with social-media-age scandals swamping the carefully honed messages of their great gatherings. None of the three principals should have much hope that the diplo-theater of a royal meeting will distract viewers from the Jeffrey Epstein outrages that have affected all three.

Trump faces anger among his own base over his decision to not release Justice Department files on the convicted sex offender. The king’s brother, Prince Andrew, was exiled from public view over his connections to Epstein. And Starmer last week sacked his ambassador to Washington, Peter Mandelson, on the eve of the state visit after Bloomberg News and the Sun newspaper published supportive emails Mandelson sent to Epstein after he pleaded guilty to soliciting a minor for prostitution.

If grand staging could once transform politicians into statesmen and meetings into history, the fractured media environment has now made such events easy to miss entirely, said David Reynolds, emeritus professor of international history at Cambridge University.

A world embroiled in the Cold War may have been glued to a Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev summit in Reykjavik, Iceland, but this week’s presidential carriage ride will largely go unnoticed unless it makes it into enough Instagram and TikTok feeds.

“In the second half of the 20th century, if you grabbed the big TV and radio outlets, you were getting a huge part of the population,” Reynolds said. “Now they won’t even see it. Politicians reach their audiences directly now.”

But nothing has disrupted the norms of diplomatic gatherings more than Trump himself. The president routinely reverses his own positions after the fact, draining communiqués and statements of their value as reflecting fixed, reliable positions. A Washington Post analysis in August showed that Trump had flipped his public stands on the Ukraine war 19 times and counting.

“That kind of yo-yo decision-making has no parallel in modern geopolitical history,” said Koehn, the leadership historian. “There were important conferences where important issues were discussed and decided that were not overturned a day later because [Joseph] Stalin had a bad hair day or saw his new poll numbers.”

Trump also bypasses the usual advance work that traditionally underpins the results of formal meetings, talks that can take weeks to perfect tone, details and agreed-upon outcomes. The sides expect this visit to produce carefully negotiated tech and energy agreements. But thornier issues, such as the final status of US tariffs on British steel and pharmaceuticals, are still up to Trump.

“These sorts of occasions have changed,” Burk said, “because now there is only one man that matters. Not even one country that matters, but one very unpredictable man.”