YOUTH DAY | How gender‑based violence is scarring South Africa’s youth

NGOs share their insights on the mental impact that GBV has on the country's younger population

Image: Pixabay

South Africa’s youth are paying a heavy mental price for a crisis that has become painfully commonplace: gender-based violence (GBV).

Whether in homes, schools or communities, exposure to inappropriate conduct, ranging from bullying and harassment to sexual assault and rape, has left a silent, psychological burden on children and adolescents.

Disturbingly, repeated exposure has led many young South Africans to become desensitised, trivialising what should alarm us all.

Desensitisation

An alarming by‑product has emerged: desensitisation. When horrific news such as rape, femicide, and assault appears daily via social media, schools and news outlets, children react with indifference.

Instead of shock, they respond with emojis and memes - emotional armour that protects but also disconnects.

In a Johannesburg Youth Research Study, 58% of adolescents admitted they “no longer feel upset” when hearing about gendered violence incidents, citing overload and helplessness. This emotional numbing undermines empathy.

A generation on the edge

According to the World Health Organization, survivors of GBV are significantly more likely to experience mental health disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, suicide and substance abuse.

In South Africa, where GBV prevalence remains among the world’s highest, the impact on youth is extremely high.

Organisations such as the South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG) report that children exposed to domestic or gendered violence are at higher risk of emotional dysregulation and behavioural problems, affecting them into adulthood.

Lifelong consequences

Early trauma from GBV exposure reshapes young minds. Studies show PTSD in children can lead to long-term issues: chronic depression, difficulty forming relationships, poor academic performance and in some cases, lowered life expectancy.

Research published in The Lancet Psychiatry indicates that traumatic experiences in childhood double the risk of mental disorders in later life.

Early intervention

Intervention works, but only if implemented early. Schools are crucial - trauma-informed counselling, safe classroom guidelines and education on respectful relationships empower youth to speak out and seek help.

Community programmes like The Soul City Institute for Social Justice have seen improved self-esteem and reduced acceptance of rape myths among teens participating in psychosocial workshops.

Family and community roles

Parents and caregivers play a vital role. Learning signs of traumatised children - nightmares, aggression, withdrawal, and responding with empathy and professional referral can prevent long-term harm. Community spaces such as youth centres can also offer mentorship, safe spaces, and access to therapy.

Policy and health systems are critical

While Non‑Governmental Organisations provide immediate support, state engagement is essential for scale and sustainability. The South African National Mental Health Policy Framework has called for provincial mental health services to integrate trauma management for youth, but implementation remains a challenge.

In order for this to succeed, more funding, training of school social workers, and access to child‑friendly professional services must become a national priority.

Rebuilding connection

Desensitisation does not signify resilience; it signals resignation. Rebuilding empathy in South Africa’s youth depends on reconnecting them to their own emotional core. Simple acts such as guided discussions, creative expression through art and writing, peer‑led support systems, all help restore trust in emotions, validate lived experiences and re-stimulate emotional engagement.

The mental toll of GBV on youth is both deep and damaging. South African organisations, educators, families and empathetic policy-makers can restore hope. Normalising therapy, encouraging emotional literacy in schools, and training professionals to recognise and treat trauma early can reshape a generation.

IOL Lifestyle

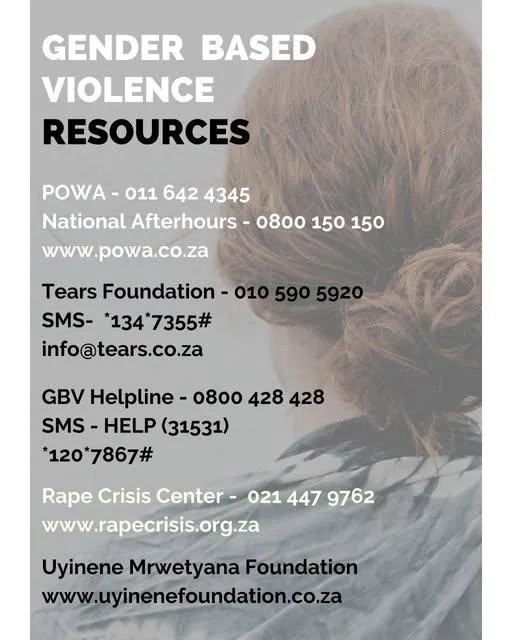

Help is available

Image: SADAG

Get your news on the go, click here to join the IOL News WhatsApp channel.

Related Topics: