Rot in the police: When the protectors are the problem for the most vulnerable

As the rot in the SAPS unravels through the Madlanga Commission - a Judicial Commission of Inquiry into criminality, political interference, and corruption in the criminal justice system - alongside a parallel process by Parliament's Ad Hoc Committee investigating allegations made by Lt-Gen Nhalnhla Mkhwanazi, IOL has investigated this disturbing phenomenon, exposing the human cost of a police force riddled with misconduct.

Image: SORA/AI

The rot within the South African Police Service (SAPS) has seeped into every corner of society, sowing deep mistrust in authorities and leaving victims without justice.

This entrenched corruption has fuelled the underreporting of crime, victimisation of the vulnerable, and a pervasive sense that the law is failing those it is meant to protect.

As the rot in the SAPS unravels through the Madlanga Commission - a Judicial Commission of Inquiry into criminality, political interference, and corruption in the criminal justice system - alongside a parallel process by Parliament's Ad Hoc Committee investigating allegations made by Lt-Gen Nhalnhla Mkhwanazi, IOL has investigated this disturbing phenomenon, exposing the human cost of a police force riddled with misconduct.

Vulnerable members of society at risk

The most vulnerable, women and children, bear the brunt of SAPS's failures. Kerr House, a shelter for abused women in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, reports that victims routinely face indifference and obstruction from the very officers tasked with their protection.

"Victims have told us that they've gone to the police station during their abuse seeking help, only to be told to go back home with the perpetrators," said a Kerr House spokesperson. "The lack of help from the police in cases is staggering; some women have said police officers simply laughed at them."

The spokesperson added that officers sometimes side with perpetrators, further endangering victims. "They call the male aside and talk. Then they tell the victims that they have friends with the SAPS whom they can pay off to drag their feet in cases of extreme urgency."

To address the crisis, she insists police officers must be trained to show empathy and take victims seriously.

Founder of Women for Change, Sabrina Walter, also sharply criticised the SAPS, accusing it of corruption and incompetence that continue to betray survivors of gender-based violence (GBV).

Walter said the problem is not that women are failing to come forward, but rather that the system is failing them after they do.

"I don't believe that women have stopped reporting cases, in fact, every 12 minutes a woman reports a rape in South Africa. Women do come forward, even after losing faith in the very system meant to protect them," she said. "The real issue isn’t that survivors aren't reporting, it's what happens after they do."

She said the organisation's accounts paint a bleak picture of police negligence.

"From the survivors we speak to every single day, most desperately want or have tried to report. They want justice. But what they encounter at police stations is often incompetence, disrespect, and a complete lack of follow-through."

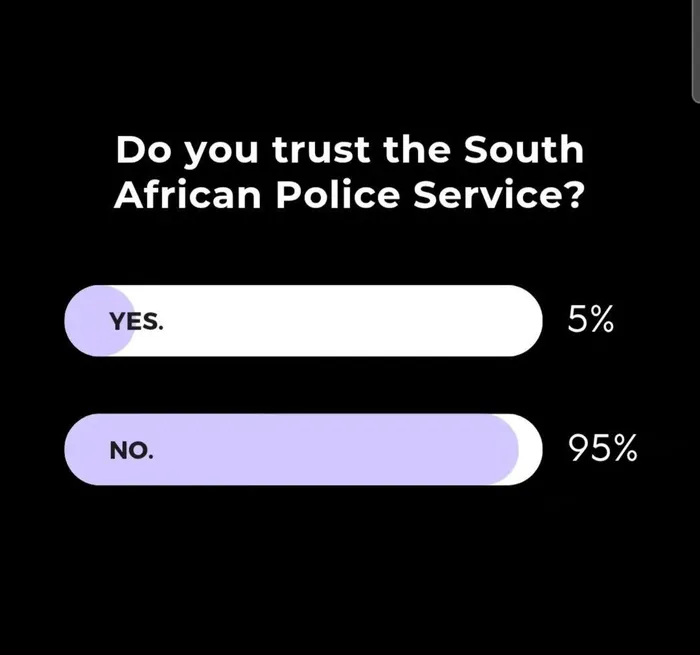

A recent Women for Change community poll where over 700 women took part underscores this distrust. According to Walter, 95% of respondents said they do not trust SAPS, 66% said their cases were dismissed, and 61% said they never heard back from the police. Only 4% of cases were ever prosecuted.

She said those numbers reveal a system that continues to fail women at every turn.

A recent Women For Change community poll where over 700 women took part underscores their distrust of the police.

Image: Women For Change

Systemic rot

In July, KwaZulu-Natal Police Commissioner Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi first sounded the alarm deep-rooted corruption within the SAPS in July 2025. He revealed extensive internal rot, including political interference, manipulation of appointments, and protection of criminal elements within the force.

This led to establishment of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Criminality, Political Interference, and Corruption in the Criminal Justice System, also known as the Madlanga Commission to investigate the explosive allegations.

Advocate Norman Arendse SC, chief evidence leader of Parliament's Ad Hoc Committee also recently cautioned that South Africa faces a pivotal moment in its democracy and must take urgent action to eliminate systemic corruption undermining the integrity of essential state institutions.

"Various attempts have been made to address the scourge of corruption, most notably the Commission of Enquiry into State Capture, the so-called Zondo Commission," he said.

He noted that the Zondo Commission uncovered how politically linked individuals exploited public procurement, state-owned enterprises, and law enforcement for personal benefit.

Arendse also highlighted the findings of the Nugent Commission, pointing out that these actions violated Section 195 of the Constitution, which requires public administration to be ethical, professional, and accountable.

In a country where the battle against violent crime remains grim, the police who should be a reliable outlet for citizens to ask for help are often feared and not trusted.

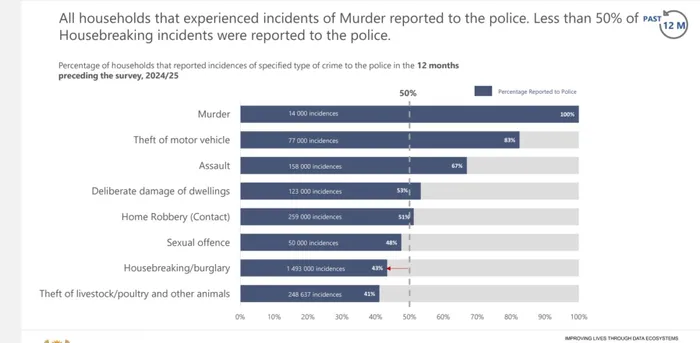

Data from Statistics South Africa’s Victims of Crime Release revealed that an estimated 59,000 households have experienced incidents of murder in the past five years and all reported to the police.

However, only half of those who experienced housebreaking/burglary reported to the police.

Statistician-General Risenga Maluleke said the findings point to a growing crisis of confidence in law enforcement. "Majority of households indicated that they did not report housebreaking incidents to the police because police could not do anything due to the lack of proof."

Data from Statistics South Africa’s Victims of Crime Release revealed that an estimated 59,000 households have experienced incidents of murder in the past five years but only half were reported to the police.

Image: Stats SA

Meanwhile, Buyiswa Ramoipone, 25, no longer sees the use of police and only goes to stations to certify documents. Ramoipone who grew up in a household with GBV saw firsthand, police fail to protect seek justice for her mother numerous times.

"Having grown up in a household with a lot of domestic violence, I learned early on that the police don't do much. Victims are forced to go back to the same situations at home.

"Dockets go missing and once that has happened, cases are over. So, the police are not really an option if I find myself a victim of a crime," she said.

Informal traders

Even those who are seeking to make ends meet through informal trading are not immune to the SAPS' shadow.

The National Informal Traders Alliance of South Africa (Nitasa) president, Rosheda Muller, said corruption within law enforcement is prevalent throughout the country and has become almost endemic.

"Many traders are reporting to us about how police are bribed for them to remain without permits and hence be illegal. Authorities frequently evict informal traders," Muller said.

In the Western Cape, Nitasa pushed for a round table with SAPS, other law enforcement, city officials, and representatives of the informal sector. Muller said these rarely happen are often not fruitful in assisting traders from corruption.

"We can't wait for a crisis to happen. There need to be good communication channels between leadership of informal traders, city officials as well as law enforcement to ensure that informal trading runs smoothly as it is one of the biggest economies in the country," she said.

How Community Policing Forums bridge the gap

In areas where police trust has significantly decreased, Community Policing Forums (CPFs) often have to bridge the gap.

Shavesh Ramnath of the Durban Joint CPF said these organisations unite police officers and community members to identify and address local crime challenges, creating partnerships that promote shared responsibility in proactive policing.

They oversee police conduct, promote openness in crime response, and enable communities to contribute to policing strategies, and rebuilding trust and respect between residents and officers.

"By involving residents in oversight roles, such as monitoring police conduct and advising on policies, CPFs ensure greater accountability, which is crucial in areas with histories of misconduct or perceived bias," Ramnath said "Police are viewed negatively by fostering partnership, improving trust or reducing crime without deeper systemic changes. Success depends on consistent implementation."

Wayne Govender who heads up the Greenwood Park CPF told IOL that residents become frustrated because the police not always around.

"Some people are hesitant to report corruption in the SAPS because they are scared as they have to come forward," Govender said. "I think people are scared that they will be victimised thereafter."

IOL News

Get your news on the go. Download the latest IOL App for Android and IOS now.

Related Topics: