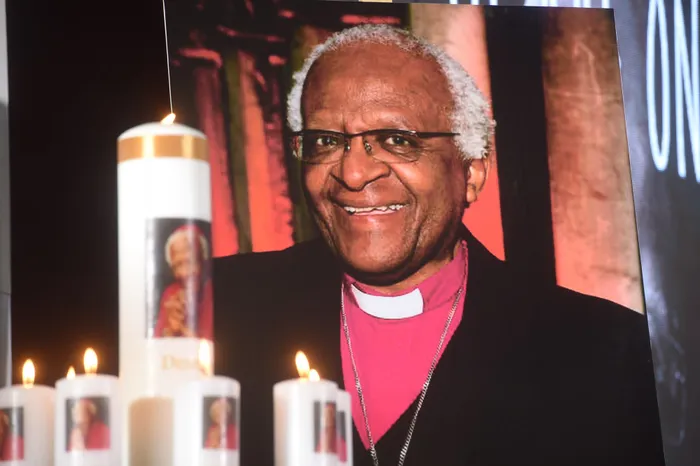

Archbishop Desmond Tutu reminds us: “There is no future without forgiveness, but forgiveness does not mean forgetting; nor does it mean impunity.”

Image: File

South Africa has not collapsed. It has been inverted. What once punished wrongdoing now protects it. What once honoured the honest now humiliates them. What once upheld truth now turns it into a liability. We are now living in what can only be called the age of the unpunished where accountability is an illusion and wrongdoing is a stepping stone not a stumbling block.

This national inversion plays out not only in the streets or in the headlines but deep within our governance systems. The medical aid racial profiling scandal, the collapse of oversight structures and recent internal disclosures from senior police leadership have laid bare how criminal sabotage and systemic corruption have infiltrated the state from within. These are not opposition claims; they are acknowledgements from those entrusted to lead. Corruption is not an anomaly. It has become the rule.

This betrayal is not theoretical. It unfolds in three distinct ways affecting the working class, black professionals and unemployed youth differently but equally destructively. For the working class, the betrayal is material and immediate. The state that should protect their safety and dignity instead leaves them exposed to criminal syndicates and collapsing infrastructure. The 2023 Public Procurement Review found that over R28 billion in state tenders were under investigation for fraud, largely in service delivery sectors such as housing, roads and water. That is not inefficiency; it is institutional neglect.

For black professionals, success itself becomes suspicious. According to a 2021 study by the South African Medical Association, black practitioners face significantly higher audit rates from medical aid administrators.

Many skilled professionals report a pattern of systemic bias where regulatory scrutiny falls harder on those without legacy networks. The very mechanisms designed to ensure compliance become traps that obstruct transformation.

And for the unemployed youth, of whom 8.9 million are not in education, employment or training (Statistics South Africa, 2024), the betrayal is existential. Young people are blamed for disengagement while entire sectors fail to absorb them. Corruption in skills agencies and jobs programmes has diverted billions away from future building efforts. According to the Auditor-General, more than R5.2 billion in irregular expenditure was flagged across youth-targeted initiatives between 2018 and 2022. These are not just numbers; they are broken promises.

What we are witnessing is not merely administrative failure but cultural amnesia paired with the death of consequence. In traditional African societies, wrongdoing was never ignored; it was confronted. But punishment was not exile. Instead, harm was brought to the centre of the community and confession was the first rite of repair. A chief who erred would step down not because he was shamed but because he was honourable.

Ubuntu, the ethic that binds us to each other, demands accountability not for punishment’s sake but for healing.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu reminds us: “There is no future without forgiveness, but forgiveness does not mean forgetting; nor does it mean impunity.” Today, however, our state culture increasingly mimics an imported logic of severance. We cut off the problem, the person or the department not to heal but to distance. We shuffle portfolios, suspend officials indefinitely or quietly retire the scandal. This “cut-off culture”, a borrowed posture from Western bureaucratic systems, offers no reintegration, no learning and no transparency. It is alien to African traditions which emphasise truth-telling and restoration over cosmetic damage control.

Some may argue that not all African leadership models upheld this ideal and they would be right. History offers many examples of rulers who betrayed these principles. But these exceptions should not define our norms. We cannot build national character on the lowest common denominator. Ubuntu is not a myth; it is an unclaimed inheritance. We dishonour it not by failing perfectly but by ceasing to try at all.

Restoration without remorse is manipulation. True Ubuntu-based justice dignifies consequence; it does not erase it. Yet the dominant model of leadership today treats admission of wrongdoing as political suicide rather than moral courage. The result is silence, secrecy and systemic rot.

The cost of corruption in South Africa is not only measured in rands and lost infrastructure; it is a theft of thenational soul. According to national estimates, South Africa loses over R186 billion annually to corruption.

During the Covid-19 pandemic alone, over R2.1bn in flagged contracts were found to be fraudulent and yet few faced trial. Surveys show that 76.2% of citizens fear retaliation for reporting corruption and 48% believe most police officers are corrupt. This is not just a governance crisis; it is a breakdown of civic trust.

In every sector, a new lesson is being taught. Speak out and you fall. Stay quiet and you may be rewarded.The next generation is internalising this code. And when truth becomes a career risk and integrity is punished, the long-term cost is not only institutional decay; it is moral disintegration.

Understanding how we got here is critical if we are to chart a path forward. South Africa’s institutional crisis is not only about leadership personalities. It is about system design. Inherited colonial architectures were repurposed for post-1994 governance without reengineering the logic of power. As Frantz Fanon warned, colonial mimicry allows the oppressor’s tools to be adopted by the formerly oppressed, producing new elites with old appetites.

Mahmood Mamdani described the post-colonial African state as “bifurcated”: liberal in language, authoritarianin instinct. We adopted the language of rights and democracy but embedded them in bureaucracies allergic to transparency and allergic to remorse.

Seen through the lens of risk governance, this is not merely a political flaw; it is a structural vulnerability. What we lack is not awareness of risk but the systems to manage it. Whistleblower protections exist on paper but are routinely violated. Ethics committees are undermined by internal loyalties. Audit findings are tabled but never resolved. And where risk detection mechanisms are present, they are often neutered by political interests.

Professor Pali Lehohla once remarked: “Institutions do not fail all at once. They collapse incrementally, when truth is first ignored, then tolerated and finally institutionalised as normal.”

That is where we stand today. As Morena Mohlomi once warned King Moshoeshoe, “You are a leader because you are a servant to the people. Once you forget to serve, you lose the right to lead.” We are losing that right, and with it, the soul of the nation.

This is a call to the honest, to the South Africans who still believe integrity matters not as a slogan but as a survival principle. Restoring public trust will not begin with national conferences or anti-corruption week slogans. It will begin with institutional courage and public visibility. That means public confessions by those who have erred. It means resignations with remorse not resistance. It means truth-and-reconciliation with consequence.

We must reimagine leadership as stewardship not entitlement. We must move from secrecy to transparency, from shame to truth, from denial to repair. Cultural restoration is not about nostalgia; it is about reintroducing accountability as a moral norm not a political calculation.

We can no longer afford to outsource integrity to the next administration, or the next election cycle, or the next commission of inquiry. Those who remain honest must step forward and hold the line not only in courtrooms but in boardrooms, classrooms and living rooms.

South Africa’s fight is not only against corruption. It is against forgetting. Against forgetting who we are, whatwe inherited and what we owe to those who still believe in a country worth saving.

This is the moment to flip the nation right-side up. Not for spectacle. Not for revenge. But for restoration.

Nomvula Zeldah Mabuza is a Risk Governance and Compliance Specialist with extensive experience in strategic risk and industrial operations. She holds a Diploma in Business Management (Accounting) from Brunel University, UK, and is an MBA candidate at Henley Business School, South Africa.

Image: Supplied

Nomvula Zeldah Mabuza is a Risk Governance and Compliance Specialist with extensive experience in strategic risk and industrial operations. She holds a Diploma in Business Management (Accounting) from Brunel University, UK, and is an MBA candidate at Henley Business School, South Africa.

*** The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of Independent Media or IOL.

BUSINESS REPORT