On August 27, 2025, the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) announced that it had reached an out-of-court settlement with Eskom after errors were made in determining revenue for the current and following two financial years.

Image: Supplied

On August 27, 2025, the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) announced that it had reached an out-of-court settlement with Eskom after errors were made in determining revenue for the current and following two financial years. This triggered sharp responses from across the industry.

Stephen Grootes described it as “the electricity pricing farce”, while Business Leadership South Africa CEO Busisiwe Mavuso said it had the “farcical effect of allowing Eskom to charge tomorrow’s customers for yesterday’s costs.” Minister of Electricity and Energy Kgosientsho Ramakgopa responded that government intends to change the entire system. The problem is that this recognition comes too late.

It is evident that the Multi-Year Price Determination (MYPD) methodology is outdated and not fit for purpose. Designed by Nersa in the early 2000s, it functioned reasonably in a system with a single supplier and no competition. Its underlying philosophy was to regulate tariffs to keep the monopoly utility in check.

At its core, the methodology rests on two components: revenue and a regulated asset base. It allows Eskom to recover revenue, to cover prudently managed costs, and a return on its asset base. But the past decade has undermined confidence that costs are being managed prudently.

As André de Ruyter highlighted in his account of his three years inside Eskom, corruption and mismanagement have eroded trust. The construction of Medupi, Kusile, and Ingula ran massively over budget, while the true costs of maintaining and refurbishing Koeberg remain opaque.

This raises questions about the reliability of the asset base valuation. The higher that number, the greater the revenue Eskom is entitled to earn. Revenue under the MYPD is a product of tariff (R/MWh) multiplied by volume (MWh). If either input is lower than expected, if tariffs are constrained or if volumes fall, then total revenue drops.

Graphic

Image: Supplied

Electricity consumption in South Africa has steadily declined since 2008, leaving demand lower than it was 17 years ago. The immediate driver was the declining reliability of supply from 2008 onwards, which curtailed economic growth. Load shedding, combined with falling technology costs for solar and batteries, accelerated the uptake of behind-the-meter installations in both residential and commercial markets. Eskom’s sales volumes declined further, creating a direct need to increase tariffs in order to maintain revenue.

Non-technical losses exacerbate the problem. This euphemism for electricity theft covers several realities: prepaid tokens sold illicitly by Eskom employees, illegal connections, and widespread non-payment by municipalities. All of these reduce the volume of paid-for electricity.

The result is that the outputs of the MYPD methodology are increasingly distorted. Nersa can attempt to “massage” the numbers to produce a politically more acceptable outcome, but the mathematics remain unchanged.

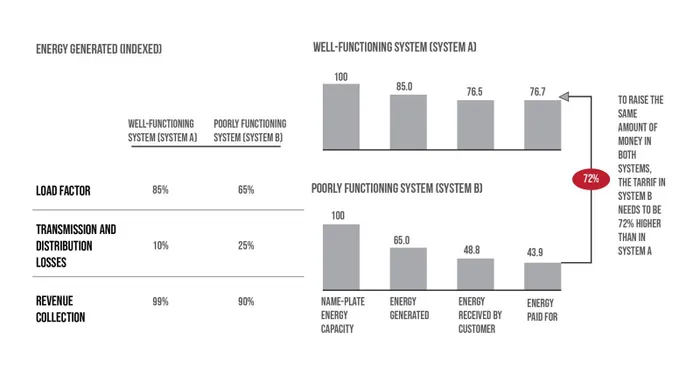

The graphic illustrates the point: in the example depicted, in a poorly functioning system, where load factors are low and technical and non-technical losses are high, tariffs must be 72% higher than in a well-functioning system.

South Africa must recognise the scale of the problem. We are operating in a poorly functioning system, and unless root causes are addressed, tariff pressures will only escalate. Electricity has become unaffordable for the average South-African and the poorest of the poor are impacted negatively. The effect of our poorly function system is compounded by a poor functioning municipal system.

What is evident, is that there are a few smaller municipalities where collaboration between private and public sector role players positively impact the delivery of basic services of utilities like electricity and water. Accurate, modern smart meters, well designed and maintained asset registers, and a customer focus underpinned by care keeps electricity tariff increases below 5%.

There are also examples of decreases in the amount of money spent to buy electricity while usage increases. We should use these examples as case studies, to improve service delivery which would create better lives for our people. The solution lies in getting the basics right. Sales volumes must increase, technical and non-technical losses must be reduced, tariff structure must be addressed and efficiency must be maximised. Only then can South Africa move away from perpetual tariff hikes and towards a sustainable electricity system.

Thomas Garner holds a Mechanical Engineering degree from the University of Pretoria and an MBA from the University of Stellenbosch Business School.

Image: Supplied

Thomas Garner holds a Mechanical Engineering degree from the University of Pretoria and an MBA from the University of Stellenbosch Business School. Thomas is self-employed focusing on energy, energy related criticalminerals, water and communities. He is a Fellow of the South African Academy of Engineering and a Management Committee member of the South African Independent Power Producers Association.

*** The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of Independent Media or IOL.

BUSINESS REPORT