South Africa's liberation movement: The tickey and the future

South Africa sits by the tracks of the global economy, watching the extraction of our sovereignty, writes the author.

Image: Wesley Ford

There is a tragic image that haunts the modern state of our liberation movement. It is the image of a child sitting in the dust beside a railway line.

The train thunders past, heavy with the wealth of the land—gold, platinum, coal, and iron ore—heading for the ports to be shipped to the bellies of foreign empires. The child does not look at the cargo. The child does not ask where the wealth is going, or why the tracks only lead in one direction—out. Instead, the child waits for the train to return from the mines, hoping that the "father"—White Capital, the Empire, the rating agencies—has brought back a small packet of sweets.

The African National Congress (ANC), a 115-year-old adult forged in the fires of struggle, has metamorphosed into this child. It sits by the tracks of the global economy, watching the extraction of our sovereignty, and when the masters of finance disembark, it does not demand ownership of the mine or the railway. It begs for mekukutoana (sugar scraps). It begs for the "sweets" of taxes and loans to fund a social wage, while the structural wealth of the nation is spirited away.

Cabral’s Verdict on the 23 Million

This infantilisation is not just a political failure; it is a betrayal of the most fundamental tenet of liberation. Amilcar Cabral, the great revolutionary of Guinea-Bissau, warned us more than five decades ago:

“Always bear in mind that the people are not fighting for ideas, for the things in anyone’s head. They are fighting to win material benefits, to live better and in peace, to see their lives go forward, to guarantee the future of their children.”

Cabral was precise. He did not say "guarantee the survival of the party"; or "guarantee a seat at the G20." He said "guarantee the future of their children."

On Friday the 12th, the Statistician-General placed a mirror before the nation, and the reflection was hideous. The Poverty Trends report revealed that approximately 23 million South Africans are living in poverty. But the dagger in the heart of Cabral’s vision is the composition of this number: children aged 0 to 17 comprise over 43% of the poor.

Nearly half of the destitute people in this country are children. When Cabral spoke of the masses fighting for benefits, he was speaking of the 10 million children currently going to bed hungry or malnourished. The ANC, hallucinating about election victories and "good stories" has failed the only test that matters. They are not guaranteeing the future; they are eating it. They are trading the nutritional sovereignty of the child for the sugar-rush of a grant system that keeps them alive but trapped.

The Lesson from Hermon: The Tickey and the Tantrum

How did we get here? How did a movement of intellectuals and warriors become a child begging for sweets? The answer lies in a story from my own childhood in the village of Hermon, Lesotho.

In the 1950s and 60s, our economic lifeline was the neighbouring town of Wepener across the border in South Africa. It was an important white man's centre. My father would often send my sister, Thakane, across the border to buy merchandise at Ha Moshemane, a shop run by a Jewish trader who had adopted a Sesotho name.

My sister, the child of a teacher, was under ten years old but could converse fluently in English. This was a marvel in our rural setting. When she entered the shop, the villagers and the trader would feign amazement at her command of the Queen’s language.

Upon her return to Hermon, Thakane would beam with pride as she narrated her transaction, expecting praise for her eloquence and the impression she had made. But my father was not listening to her story. He was carefully inspecting the merchandise and counting the change.

Alas, while my sister awaited accolades, my father noted that Moshemane had short-changed her by a tickey (three pence).

His rebuke was sharp and it rings through the decades to the Union Buildings today: “Whilst you thought Moshemane was admiring your mastery of English, he was using your stupidity to take the tickey back.”

The G20 and the Missing Change

For thirty years, the ANC government has been my sister Thakane.

They have travelled to Davos, to the G7, and to the G20. They have spoken the "English" of neoliberalism fluently. They have been praised by the IMF and the World Bank for their "sound fundamentals" and their "prudent fiscal management." They have preened on the world stage, drunk on the flattery of the West.

But while they were being applauded for their diplomatic etiquette, the global financial system—the modern Moshemane—was taking the tickey back.

The "tickey" is our financial sovereignty. It is the ability to direct credit to the poor, to industrialise, to stop illicit financial flows. The National Planning Commission (NPC) tried to point this out. They prepared a foundational paper on the macroeconomics of financialisation, warning that the current system, guarded by the "empire appendages" of the National Treasury and the Reserve Bank, was eating us for lunch.

But the ANC refused to listen. They were too busy waiting for the G20 meeting in Miami. And now, when Donald Trump sneers and tells them they are not welcome at the table, they throw a tantrum. They protest that they should be there. They beg for a petition. They are fighting for the right to be flattered, while the tickey is gone.

The Railway Line of Consequences

This brings us back to the railway line. The 23 million poor are not interested in whether the ANC has a seat in Miami. The 43% of children living in poverty cannot eat a diplomatic communiqué. They are the victims of a government that chose the "sweets" of foreign approval over the hard work of structural transformation.

The transition from the forensic hope of the Zondo Commission to the crude extortion of the "Cat Matlalas" is the result of a state that has forgotten how to produce wealth and only knows how to consume the scraps.

We have a 115-year-old child sitting in the dust, holding an empty bag of sweets, while the train of the future disappears over the horizon.

It is time for the adult to wake up. We do not need Moshemane’s applause. We do not need a seat at Trump’s table. We need to audit the change. We need to realize that the "macroeconomics of financialization" is the mechanism of our theft.

Cabral is watching. The 23 million are waiting. And they are not asking for sweets. They are asking for the tickey back.

Dr Pali Lehohla is a Professor of Practice at the University of Johannesburg, among other hats.

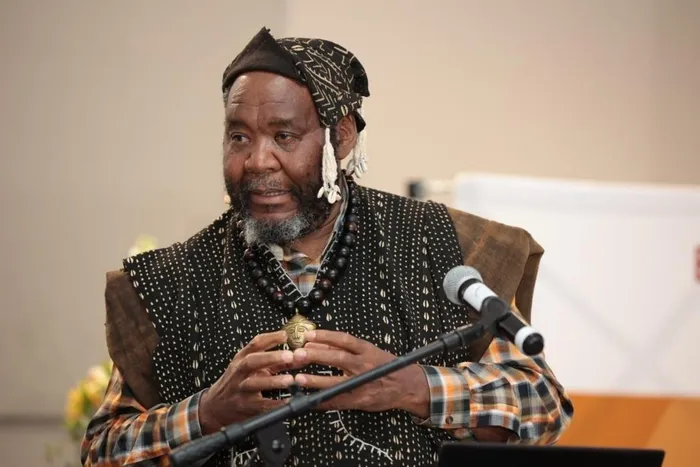

Image: Supplied

Dr Pali Lehohla is a Professor of Practice at the University of Johannesburg, a Research Associate at Oxford University, a board member of Institute for Economic Justice at Wits and a distinguished Alumni of the University of Ghana. He is the former Statistician-General of South Africa.

*** The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of Independent Media or IOL.

BUSINESS REPORT