Explore the growing trend of private assets in investment portfolios, understand the benefits and risks, and learn how to navigate this evolving market as an individual investor.

Image: File

Over the next few years, individual investors are expected to increase their allocation to private markets, in some cases potentially approaching levels seen by various types of institutional investors. The compelling return history for private market investment is clearly a key motivator for these allocations. Schroders Capital research shows this is the main reason institutional investors enter private markets, and we have no reason to believe individual investors think any differently.

Over the past five years, smaller clients have also been offered more options to invest in private markets thanks to product development, changing regulations, and technological advancements. New regulated fund structures such as the long-term asset fund (LTAF) in the UK, the European long-term investment fund (ELTIF) in Europe, and UCI Part II have been a game changer for accessing private markets, as well as for the increased use and further development of evergreen open-ended funds.

While promoting access to private markets with these new structures, regulators around the world have also been tightening rules to protect smaller investors. For example, in the UK, clients must confirm they meet certain investment criteria, undergo a suitability review by their financial advisor, and have a 24-hour cooling-off period to reconsider their decisions. The South African regulator requires investors to meet the criteria of a qualified investor as per the definition in section 96(1)(a) of the South African Companies Act, No. 71 or 2008 as amended, and/or to have a minimum of R1 million to invest in terms of section 96(1)(b) of the South African Companies Act.

Bain & Company estimates that by 2032, 30% of global assets under management could be allocated to alternatives, with a large chunk in private assets. While private investors currently allocate only up to 5% of their portfolios to private markets, we anticipate that the gap with institutional investors will narrow significantly over time, and private markets will become commonplace.

The growing appeal of private markets

Of course, returns aren’t the only reason to use private assets, even if it’s high on the client's agenda. Characteristics like stable income and genuine diversification, which have the potential to significantly enhance overall portfolio resilience, add to the appeal.

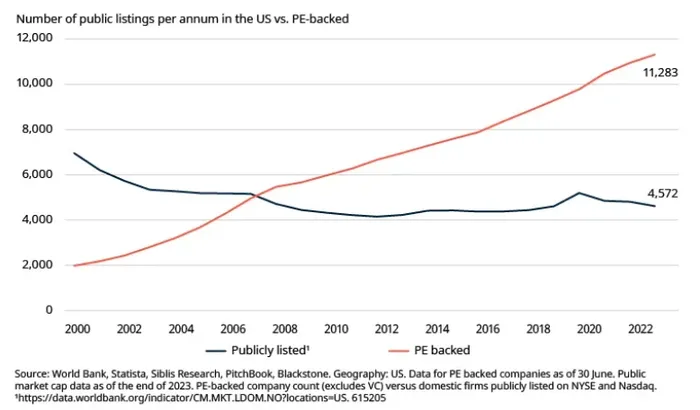

It is also about the opportunity set. In public markets, there is an increasing concentration of stocks, with more than 30% of the S&P 500 dominated by just a handful of companies, leading to a narrower range of options. In contrast, the number of private companies, and those staying private for longer, continues to grow. Private companies in the US with revenues of $250 million or more now account for 86% of the total. Additionally, the number of public listings in the US has more than halved over the past 20 years compared to the period from 1980 to 1999, highlighting the shift towards private market opportunities (see chart). In South Africa, the last five years have seen an average of 24 companies delist from local stock exchanges on an annual basis, although 2024 showed a significant slowdown in this rate as only 11 companies exited the public market. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange is also highly concentrated, with a few large companies dominating the index.

And it’s not just a matter of numbers. Private companies tend to be more agile and innovative in their operations compared to public companies, and they can access opportunities in sectors where public companies have limited or no reach. For example, the new US tariff policies are likely to affect both public and private companies, particularly those vulnerable to supply chain disruptions. However, private companies tend to be more flexible in restructuring their supply chains to adapt to these changes, potentially avoiding cost increases. Nevertheless, companies heavily impacted may still face higher costs, affecting profitability, and therefore valuations and deals.

Public markets continue to shrink, and companies are staying private for longer

Number of public listings per annum in the US vs PE-backed.

Image: Supplied.

Once the decision to allocate to the asset class has been made, what is next? How do investors actually start their private assets journey, and what can they expect the journey to look like?

Pacing is different

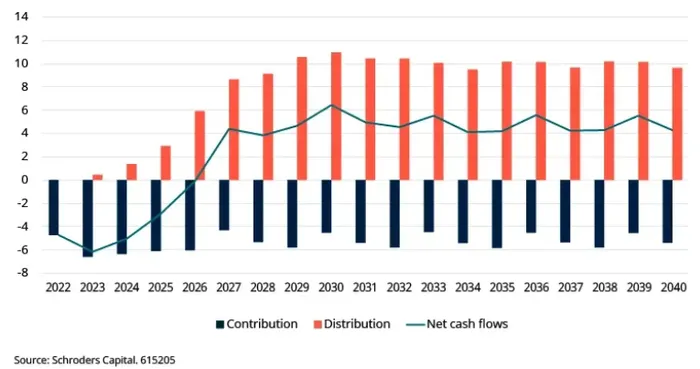

One of the key differences with private asset investment is in the pacing of capital deployment. With no immediate secondary market to provide liquidity, allocations can and should be structured to, in a sense, create their own liquidity. Structured correctly, private asset allocations can become “self-sustaining” over time, with distributions and income funding new investments to maintain a target allocation. What does that mean in practice?

Many fund managers, or general partners (GPs), raise capital every year in what is known as “vintages”. Each vintage represents a discrete fund that has an investment phase and a harvesting phase. The investment phase is when the capital is put to work, typically for about 3-5 years, depending on which part of the private assets market it’s in, and what the market backdrop is like. The harvesting phase is when the invested assets are exited, generating capital that can be distributed back to investors. This is typically around 5-7 years after the investment is first made in what is known as an “exit”.

Private equity managers will use the term “exits” because, while selling an asset is an option, it’s only one of many options available. The routes to exit are varied but most commonly the company is either floated in an IPO (initial public offering), sold to another corporate buyer or private equity investor, or sold into a continuation vehicle. In private debt, the fund managers (there is often a cohort of lenders) will structure lending in such a way that the capital is returned at the end of a defined timeframe, having received the cashflows. These cashflows can then be used to refinance (‘re-up’ is a term often used) subsequent vintages.

Private assets portfolio becomes self-financing after 5-7 years

Private assets portfolio becomes self-financing after 5-7 years.

Image: Supplied.

In recent years, new exit routes have emerged, especially in the secondary market, with the continuation vehicles mentioned above. That’s because these deals allow the GPs to provide a liquidity mechanism to their existing investors, the limited partners (LPs), while at the same time holding onto key assets for longer to maximise value. Continuation funds have evolved to become a common strategy for GPs to hold onto high-performing assets, or pools of assets, beyond the life of the original fund.

Vintage years, consistent deployment, and the impact on returns

A vintage year allocation approach has the benefit of mitigating the risk associated with market timing. Despite our optimism for the mid-to-long-term outlook for private assets, the near term is undoubtedly going to be challenging for many investors, and keeping up a steady investment pace may be difficult.

While exit and fundraising activity seemed to have bottomed out in 2024 following a prolonged slowdown since 2022, risks and uncertainty in markets have increased sharply since the start of the year. As we pointed out above, this is mainly due to the uncertainties caused by the US government policy changes and the impacts these may have on economies and markets.

In addition to broader concerns over performance, when markets fall, some investors face the “denominator effect”. Private assets tend to correct less than other more liquid asset classes due to the way they are valued, so their relative weight in an investor’s portfolio tends to increase when markets fall sharply. This can limit investors’ ability to make new investments into the asset class and maintain a determined percentage allocation.

Nevertheless, research suggests investors don’t have to shy away from new investments in periods of crisis or recession.

A recent analysis from Schroders Capital shows that private equity consistently outperformed listed markets during the largest market crises of the past 25 years. Despite challenges such as high interest rates, inflation, and economic volatility, private equity outperformed public markets and experienced smaller drawdowns, with distributions becoming less volatile over time.

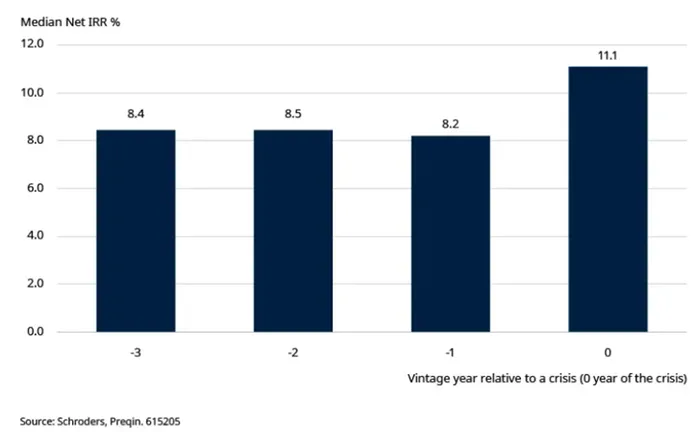

Meanwhile, recession years tend to yield vintages that perform exceptionally well.

Structurally, funds can benefit from “time diversification”, where capital is deployed over several years, rather than all in one go. This allows funds raised in recession years to pick up assets at depressed values as the recession plays out. The assets can then pursue an exit later on, in the recovery phase, when valuations are rising.

For example, our analysis shows that the average internal rate of return (“IRR”) of private equity funds raised in a recession year has been higher than for funds raised in the years in the run-up to a recession, which, at the time, probably felt like much happier times. For private debt and real estate, there are similar effects. For infrastructure, the effects should also show a similar pattern; however, longer-term data is limited in this part of the asset class.

Private equity vintage performance (average of median net IRRs)

Private equity vintage performance (average of median net IRRs).

Image: Supplied.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

Source: Preqin, Schroders Capital, 2022. There are 9,834 funds in the Preqin database. Only funds with vintage years after 1980 and 2017 are analysed. 220 funds that were out of distribution were excluded, reducing the number of funds in our universe to 3,400. Private equity-only investments, venture debt, and funds of fund strategies have been excluded.

Pacing illustration for an investor

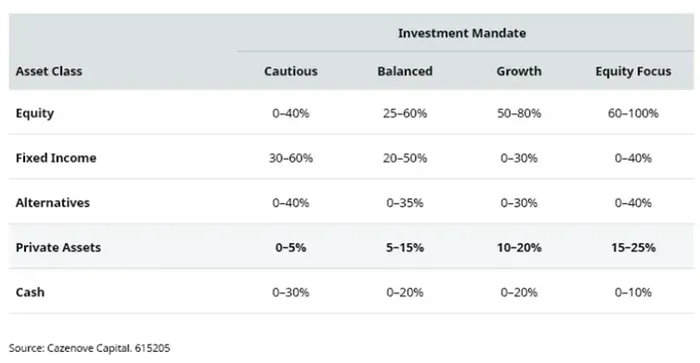

Appropriate allocations to private assets will, of course, vary by client and will always be led by overall suitability. Important factors such as a client’s overall income and expenditure, time horizon, investment understanding/experience, appetite for borrowing, and ability to tolerate illiquidity are all factors we consider when deciding on exposure to private assets.

For the sake of illustration, though, let us assume all individual clients fall within one of four risk brackets: cautious, balanced, growth, and aggressive. What would the investment pacing look like for the private asset allocation?

For a client on a growth risk mandate (this would mean a typical exposure to equities of between 50-80%) who has a good understanding of investments, a target allocation of 20% might be appropriate across private debt, private equity, and real estate.

How private assets could fit within a portfolio

How private assets could fit within a portfolio.

Image: Supplied.

It’s important to note that the nature of investing in private assets means that allocations should be built up over time to ensure vintage diversification and that we explicitly recommend diversification by investment and vintage. While we want to diversify by asset class, we also suggest spreading investments across a range of structures.

This usually depends on the investable assets and the investor's ability to accept illiquidity, noting that private investors could benefit from different structure types. For example, clients with large investable asset bases that have the ability to lock up their money for 10 years plus, can use the traditional routes, such as closed-ended structures. Otherwise, clients with lower minimum entry points and with an uncertain time horizon are able to use “evergreen” open-ended funds: these funds do not have a pre-determined lifespan and can run in perpetuity, recycling investment proceeds and raising new capital as required. While clients investing in evergreen funds are able to access their money periodically, they need to understand these are still long-term commitments and that there are established limits and rules on when and how much they can withdraw.

It’s important that investors be educated and prepared for their allocation to be left untouched for an extended period. Private equity funds typically run for at least seven years, during which time the allocation will not be liquid. The realisation of the assets will also take several years, tapering down in the same way the allocation is gradually ramped up. This is why a complete, ongoing understanding of a client's overall financial position is crucial when considering building a private assets allocation.

Private Assets - Investment risk: Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. Investors should only invest in private assets (and other illiquid and high-risk assets) if they are prepared and have the ability to sustain a total loss of their investment. No representation has been or can be made as to the future performance of these investments. Whilst investment in private assets can offer the potential of higher than average returns, it also involves a corresponding higher degree of risk and is only considered appropriate for sophisticated investors who can understand, evaluate, and afford to take that risk. Private Assets are more illiquid than other types of investments. Any secondary market tends to be very limited. Investors may well not be able to realise their investment before the relevant exit dates.

* Krekis is a portfolio director at Cazenove Capital, part of the Schroders Group.

PERSONAL FINANCE