How the Two-Pot system is affecting South African retirement funds

South Africans are increasingly withdrawing from their retirement savings due to the Two-Pot system, raising concerns about long-term financial stability and the implications for the economy.

Image: File photo.

The Two-Pot system, designed to offer South Africans a lifeline in the event of a serious rainy day, has seen such high demand for withdrawals that experts are concerned that people will have only two-thirds of their savings left.

Changes in the law, which came into effect last September, made it possible for people who have retirement savings to access a portion of them now, with the rest remaining invested until they stop working. Under the changes to the law, one-third of retirement savings went into a pot from which withdrawals could be made, and that allows people to pull out money once a year in an amount between R2,000 and R30,000.

But there are drawbacks. In addition to the fact that the cash that is taken is subject to tax, any amount due to the South African Revenue Service (Sars) in unpaid tax is deducted from the payout. Those are the short-term consequences – longer-term, withdrawals now will exacerbate South Africa’s already low savings rate. South Africans have a negative savings rate of 1.2%, according to Trading Economics.

Hwalani Mabaso, executive of everyday advice and distribution at Absa Advice and Investments, says that the tax on withdrawals “came as a rude awakening to some who saw their expected payout significantly reduced. Financial service providers also had to play catch-up, with reports of some charging excessive admin fees. The learning curve was steep – not just for members, but for the industry itself,” she notes.

Michelle Hawkins, senior tax expert at PKF Octagon, says that Sars has collected R15 billion in taxes from Two-Pot withdrawals, of which R1bn was in overdue payments.

Mabaso’s calculations indicate that a R30,000 withdrawal could mean R22,000 lands in accounts after withholding tax, which doesn’t take into account any overdue tax.

One of Two-Pot’s most vocal detractors is former statistician-general, Pali Lehohla. Lehohla tells Personal Finance that pulling money out of an already meager savings pool detracts from fund managers, such as the Public Investment Corporation, being able to invest in key sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, and mining.

This, Lehohla says, undermines the architecture of pension funds, adversely affecting South Africa’s growth prospects. “If you draw from it, you destroy a nation.” Gross domestic product (GDP) gained a better-than-expected 0.1% in the first quarter of the year after reaching 0.6% in 2024.

Phil le Feuvre, member of the South African Reward Association, says that nearly R57bn has been withdrawn from retirement funds since last September. For context, the sector was worth about R4.6 trillion in 2022, the latest research available.

Le Feuvre says there have, so far, been almost four million withdrawals, out of an estimated 18.6 million retirement fund members in South Africa. Of these, about 12% were repeat withdrawals following the start of the new tax year in March, he adds.

Hawkins is concerned that there have been repeated withdrawals. “This behaviour raised concerns that the system might be used more as a revolving credit facility than an emergency buffer,” says Mabaso.

Yet, Mabaso says the “bold and necessary reform” has benefitted those South Africans who are battling rising costs as it has been a “financial lifeline”. She says, in addition to making emergency funds available without totally sabotaging long-term retirement savings, it has also had a macroeconomic benefit.

“Analysts estimate the system injected R40bn to R100bn of liquidity into the economy, boosting consumption and tax revenue, thanks to SARS collecting income tax on withdrawals. Some reports even suggest it could contribute up to 0.5% to GDP growth in 2025,” Mabaso says.

Mabaso says, however, that the “freedom to withdraw comes at a cost”. She explains that someone who pulls money out each year could reduce their retirement nest egg by 30% to 33%, which could be “a potentially devastating impact in old age”.

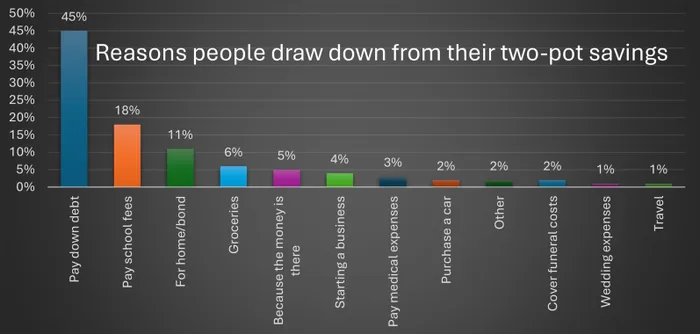

Hawkins says research conducted by various financial institutions has shown that most drawdowns are going towards debt, school fees, groceries, and other basic necessities. “The pressures of the cost of living are the key driver for the two-pot withdrawals,” she says.

“Evidence suggests that a portion of the withdrawals is being used to pay off high-interest loans or, worse, fund consumer purchases, defeating the system's intent to promote financial resilience,” Mabaso explains.

Le Feuvre adds that some beneficiaries used funds as a deposit to buy a car, leading to increased debt in the long run. “Overall, the funds helped consumers reduce financial strain but also contributed to new credit uptake.”

Mabaso says, like all policy tools, Two-Pot’s success depends on how wisely it’s used. She says people need educational support to understand tax, compound interest, and long-term implications. “Handled with care, the system could offer South Africans the dignity of choice and financial resilience.”

Reasons people draw draw down from two-pot.

Image: Source for graphic: Le Feuvre

PERSONAL FINANCE