The Gini Coefficient: A flawed measure of inequality

Analysis

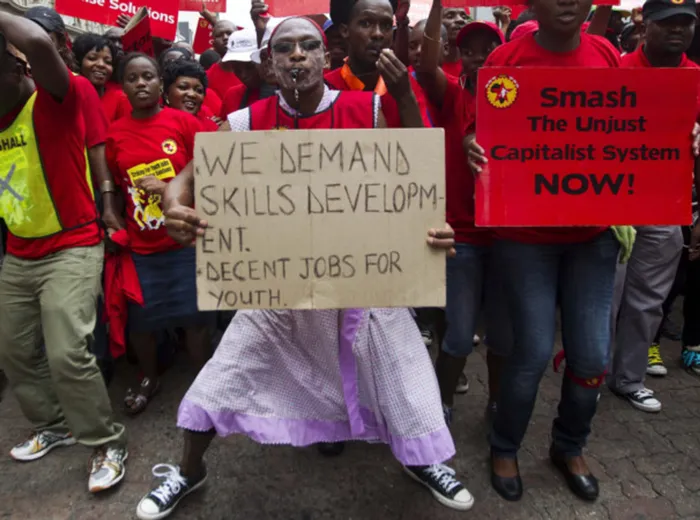

Is South Africa the most unequal country in the world?

Image: Independent Media Archives

IS South Africa the world’s most unequal country? No. The numbers are lying to you. The Gini Coefficient, the flawed metric behind this damaging myth, ignores billions in black wealth, millions of social grants, and one of Africa’s fastest-growing middle classes.

Today, we expose why this outdated statistic is holding South Africa back — and why we need a new way to measure real progress.

“Ask just about anyone in South Africa about the Gini coefficient, and they will either stare at you blankly or tell you only two things: one, the Gini coefficient is the measure of income inequality in society, and two, that South Africa is the most unequal society in the world based on that measurement.”

Few have questioned whether the Gini coefficient is a reliable measurement of wealth and income inequality, or if South Africa’s ranking is as dire as claimed.

This single statistic has become gospel in policy debates, invoked to justify everything from wealth taxes to radical economic interventions. But how reliable is the Gini coefficient? And does South Africa’s notorious ranking tell the full story, or has it become a misleading political crutch?

Part of the reason for its uncritical acceptance is that criticism is stifled by psychological tactics akin to those used by cult leaders: framing dissent as “anti-poor” or pro-status quo. Who wants to be branded as “for inequality” or to challenge a statistic endorsed by institutions like the World Bank? Compounding the issue, few understand the Gini beyond South Africa’s poor ranking. As a result, the “cult of the Gini coefficient” persists.

What Is the Gini Coefficient?

The Gini coefficient is a statistical measure (between 0 and 1) that quantifies how much a dataset deviates from perfect equality. Zero represents absolute equality; one represents absolute inequality.

Developed in the early 20th century by Italian statistician Corrado Gini, it can measure inequality in wealth, income, height, weight, and more. However, as Prospect magazine notes, Gini himself was no champion of equality — he supported Mussolini, fascism, and eugenics.

For most of the 20th century, income inequality was a niche statistical exercise. It gained prominence after the 2007–08 financial crisis and Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014), which argued that wealth in developed nations was increasingly concentrated in the top 1%.

In a sharp critique, Shaun Read (founder of Read Advisory Services) dismantles the Gini’s credibility, calling it an oversimplified, misused metric. He argues it has become a “cult-like” statistic, shielded from scrutiny by fear of being labelled “anti-poor”. Its key flaws include:

- It Ignores Critical Context

- Based on Outdated, Inconsistent Data

- It Masks Progress

- It Doesn’t Account for Wealth Mobility

The Real Question: Should We Still Care About the Gini?

Read’s central argument is damning: The Gini is a Political Tool, Not a Policy Guide. Fixating on it risks punitive redistribution (like wealth taxes) instead of addressing root causes — skills gaps, education, exclusion from capital, and a stagnant economy. As Read puts it: “If everyone in poverty earns a living wage, educates their children, and accesses opportunities, does the Gini rating even matter?”

It may be time for South Africa to retire the Gini and focus on outcomes, not outdated statistics.

Since 1994, South Africa has undertaken one of the most ambitious social and economic transformations in modern history. Through welfare policies, B-BBEE, affirmative action, and free education, the ANC-led government has:

- Lifted millions from absolute poverty.

- Drastically reduced child malnutrition.

- Built Africa’s largest Black middle class.

No other African nation — and few in BRICS — can match South Africa’s social protections, especially given its robust democracy. Free healthcare, no-fee schools, nutrition programmes, and NSFAS funding are untold successes.

Yet institutions like the IMF and World Bank label South Africa “most unequal” using the flawed Gini coefficient. By contrast, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and others appear “more equal” simply because their populations are overwhelmingly poor, with no grants or worker protections.

No African country has grown a Black middle class as rapidly as South Africa. Policies like B-BBEE and NSFAS have enabled generational wealth shifts, producing 6 million Black middle-class households (up from 350 000 in 1993) and Black millionaires and professionals (via B-BBEE and NSFAS). The Gini ignores this progress, fixating on wage gaps instead of asset growth.

The current system is rigged against the Global South. South Africa must pioneer a framework that accounts for wealth accumulation (property, stocks, businesses), social wage value (grants, education, healthcare), and informal sector contributions (spaza shops, taxis, stokvels).

Without this, the IMF will keep using flawed data to justify policies that keep Africa poor.

South Africa’s strides in poverty alleviation and Black middle-class growth demand a reframed discourse. The Bretton Woods institutions’ focus on income inequality (not wealth) may aim to keep Black South Africans as wage-earners, not capital-owners.

While the Gini paints a stark picture, it ignores the complexities of South Africa’s progress. South Africa must reject IMF austerity and lead the development of an African-centric inequality metric — one that highlights real progress, not abstract calculations. In doing so, it can reshape global narratives on economic growth and equality.

* Phapano Phasha is the chairperson of The Centre for Alternative Political and Economic Thought.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, IOL, or Independent Media.