ANALYSIS | The slow death of prime and what it means for your home loan

The South African Reserve Bank wants to do away with the prime lending rate.

Image: ChatGPT

South Africans could one day pay less for their home loans – but they could just as easily end up paying more.

That uncertainty sits at the heart of a new proposal from the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) to phase out the long-standing prime lending rate, a move that may sound technical but carries potential consequences for borrowers.

In its latest discussion paper, SARB has floated the idea of scrapping prime as the standard reference rate for loans, replacing it with direct repo-linked pricing.

The proposal follows closely on another major policy shift championed by SARB governor Lesetja Kganyago of moving South Africa’s inflation target to 3% with a narrower band, instead of the previous 3% to 6% range.

The Bank argues that lower, more stable inflation should reduce borrowing costs over time.

Inflation targets do not automatically deliver lower interest rates. They influence expectations, credibility and long-term pricing dynamics – but real-world outcomes still depend on economic growth, global shocks and fiscal stability.

Similarly, removing prime does not guarantee cheaper credit.

Prime has historically functioned as a widely recognised benchmark. Even if poorly understood, it has provided consumers with a simple anchor for judging loan pricing.

In a repo-linked system, that familiar reference point disappears.

Banks would gain greater flexibility in how they structure margins above the repo rate — a development that could sharpen competition for low-risk borrowers but potentially widen pricing differences for others.

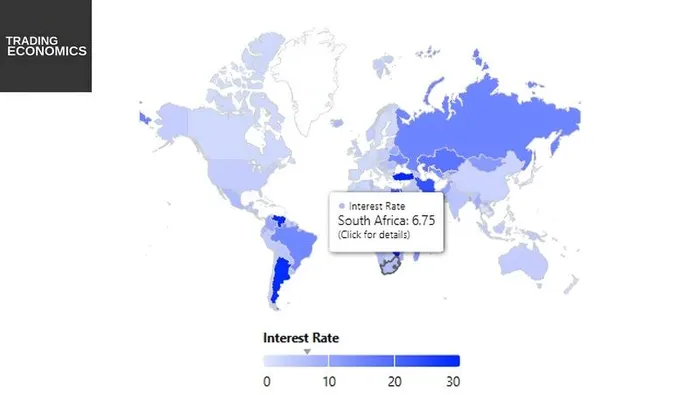

Trading Economics refers to South Africa's interest rate as the repo figure and not prime.

Image: Trading Economics

Borrowers with weaker credit profiles may find margins rising as banks lean more heavily into risk-based pricing models.

What was once framed as “prime plus 3%” could become “repo plus 6%”, making the bank’s risk premium more visible – and potentially more variable.

Banks would also find themselves under a brighter transparency spotlight.

In a repo-linked environment, the margin a bank adds, covering risk, funding costs and profit, becomes more visible than under the traditional prime-based structure.

What has long been framed as “prime plus” or “prime minus” may increasingly be interpreted by borrowers as a clearer markup above the policy rate, potentially prompting closer scrutiny of pricing differences between institutions.

Greater transparency, however, does not automatically translate into better outcomes. While some consumers may benefit from easier comparisons, others could face wider variations in margins as banks lean further into risk-based pricing models.

There is also the behavioural risk.

Prime has served as a buffer in consumer psychology. Repo rate changes feel abstract to many households, while prime movements have carried more immediate resonance.

Direct repo-linked loans may make rate hikes feel sharper, even if the underlying adjustment is mathematically equivalent.

For heavily indebted consumers, perception can influence spending, confidence and financial stress.

Another concern is complexity.

Prime, despite its flaws, has been easy to communicate. Repo-plus pricing may require greater financial literacy to interpret effectively, particularly for consumers comparing loan offers across institutions.

Greater transparency does not always translate into greater understanding.

However, removing a common benchmark could make it harder for borrowers to gauge whether pricing is competitive. Without prime as a shared reference, assessing what constitutes a “good deal” may become less intuitive.

While banks would be expected to convert existing contracts in a way that preserves their economic terms, future lending dynamics could evolve differently.

Margins may become more fluid.

Pricing dispersion between banks may increase.

And consumers may face a steeper learning curve in understanding how interest rates affect their debt.

The Reserve Bank maintains that the proposal is aimed at modernising the rate framework and improving monetary policy transmission.

Yet as with the shift to a 3% inflation target, the benefits, if realised, are likely to emerge gradually rather than immediately.

For now, borrowers are unlikely to see instant relief in monthly instalments.

But neither are they guaranteed protection from future pricing shifts.

What appears to be policy plumbing could, over time, reshape not only how loans are priced, but how South Africans experience the cost of credit.

IOL BUSINESS

Get your news on the go. Download the latest IOL App for Android and IOS now.

Related Topics: